When I was 15 I had my heart broken. My first love had dumped me and the world was ending. What had I done wrong? My mind raced with possibilities and answers to sad lines of questions. Surely there was a simple way to fix the problem. I moped around the house, listening to laughably angsty Dashboard Confessional songs (“My heart is yours to fill or burst to break or bury, or wear as jewelry, whichever you prefer”), going on long runs by myself, blackout drinking with friends, self-mutilation, and being generally morose. My mom would roll her eyes and give her 10,000 ft view: there will be more girlfriends.

I didn’t believe her at the time, and looking back my behavior seems so silly and overdramatic. Of course, there would be other girlfriends. Of course, that heartbreak wouldn’t last forever. Of course, there would be more heartbreaks. But at the time, it was so painful and real. I couldn’t imagine loving anything or anyone else, simply because I hadn’t experienced anything else.

Back then, the only thing to heal my broken heart was to fall for someone else. A new love interest would occupy my attention span and eventually, I forgot about the pain of a broken heart.

I actually had no idea what it was to love as a teen. Truly, I couldn’t understand how much hard work goes into loving someone or something. The challenge is waking up every day, resetting, and rededicating with your whole heart. In the lull of the mundane, it’s easy to go through the motions of emotion, thinking about my to-do list or daydreaming of other things.

Bike racing is a labor of love and with anything that you love, there has to be heartbreak. My friend Hannah wisely said, “The bigger the dream, the bigger the heartbreaks along the way.” I have sacrificed so much of my money, time, energy, and relationships. In exchange, I’ve received a lot of scars, new friends, and some really precious memories. Similar to romantic relationships, I’ve broken up with bike racing before.

I moved to Northwest Arkansas in 2016 to take road riding more seriously. For the last couple of years, I had been living in Kansas City and worked my way from Cat 5 to Cat 3 in quick succession. I loved road and criterium racing—the speed, the strategy, and the timing. The delicate dance had to be just to end up at the top. In Arkansas, I put in hard work and went to the right races, upgrading to a Cat 2 after the season. I raced a handful of Cat 1/2 criteriums and realized how much more work and money the next step was going to take. I would need to rededicate myself to training but also travel a lot more for races to get my Cat 1 upgrade. And then what? Disenchanted, I stopped racing altogether.

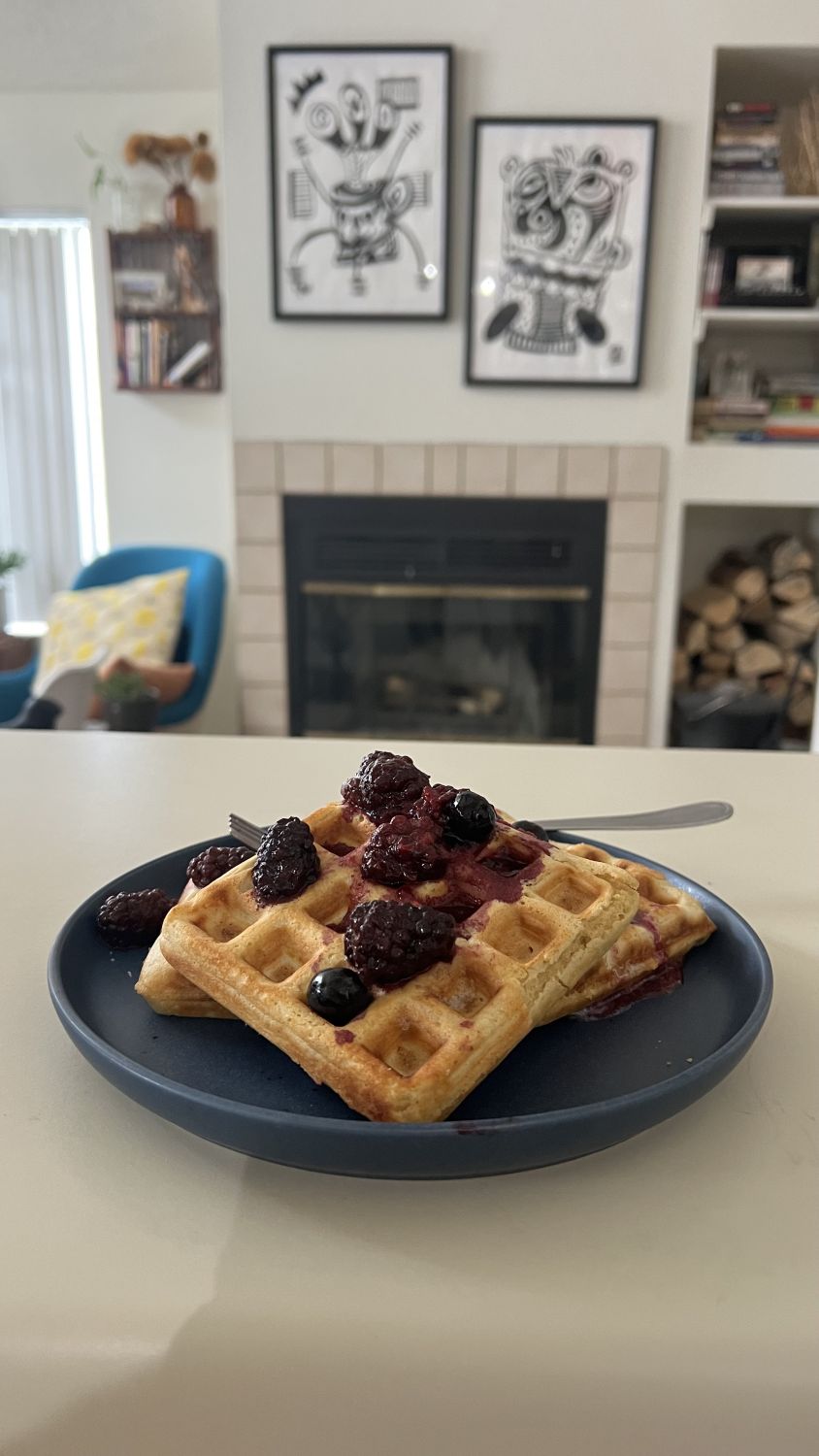

When I describe my passion for long-distance racing, people have asked me, “Why?” and that’s a funny question when you’re in love—it’s a little indescribable. At times, it can feel like the easiest thing in the world and then it can also feel like the most punishing. I can list a hundred different ways that bike racing is fulfilling for me, but it won’t quite capture my love of the sport. I know that when it’s good, it’s really, really good. The Process is a long one, day in and day out. Hours of riding, hours of bike maintenance, hours of body maintenance, the right food, experimenting with bike setups and fuel strategy. When it all comes together, it’s not just a celebration of one moment or event, but of The Process.

People’s reaction to Lachlan winning Unbound 200 has been so wholesome. Finally, a champion that everyone can celebrate. Why is this feeling so universal? Lachlan’s story has been in cycling media everywhere. He tried his hand at World Tour racing and was burnt out by the grind. Shifting his focus, he raced in the emerging American gravel scene and Team EF believed in him enough to support him. Lachlan comes off as humble and personable while still achieving superhuman feats, like unofficially blasting through the Tour Divide record. Lachlan is the everyman, and we see our own reflections. “That would be my story.” Bike racing takes its pound of flesh in any way it can, so when we see someone pay their dues year after year and finally take the top step, it’s like we all won. In my own successes, I feel that energy from the people cheering from my corner.

My crash at Unbound happened in the blink of an eye. One moment I was on top of the world, feeling like I was finally proving myself in one of the toughest bike races. I remember we crested over the top of Dawson’s Hill, picked up speed and the road turned into a gnarly, ledgy rut. My body tensed up when I saw I was on a really bad line. My front tire was a bit low on pressure and I smashed into the edge of a jutted rock and instantly deflated. The momentum catapulted me from the bike going from 22 mph to zero. I lay on my back for a second stunned at the sudden turn of events. In a combination of agony and frustration, I let out a wild scream before remembering I was a danger to the folks behind me. I quickly scrambled to my feet to drag my bike out of the way and assess any damage. Nothing on the bike was broken, just the levers turned inward. Frantic, I grabbed my CO2 to start on my front tire when my helmet slid down over my eyes, no longer holding to my head. When I took it off, I knew my race was over. Underneath the huge dent on the back, the styrofoam had cracked in multiple spots. For a moment, I considered the option of charging forward but knew the serious repercussions of concussions. Some concussions won’t show the worst symptoms for a few hours. As a high school cycling coach and advocate for rider safety, I understood the gravity of head injuries and the importance of prioritizing health over ambition. Ignoring my own advice and charging forward would be reckless and stupid. Dazed and dejected, I rolled my Donkey backward on the course to a spot with cell service to call my girlfriend Heather for a pickup.

The verdant green Flint Hills were putting on an apology show. Dusk sunlight streamed through clusters of clouds, highlighting the deep valleys and luscious hilltops. As much mettle and grit as one thinks they have, this land stays stoic and unwavering in its slopes. My existence is a blink of an eye with the tens of thousands of years of Dawson’s Hill and my inexperience is apparent. The hill does not care about this stupid race, but I feel some consolation while I saunter back to the gravel road, the vast rolling landscape reminding me of the stunning beauty of Kansas. In 2024, I am not the first Kansan to win Unbound XL, but I will be back next year. The first conversation with Heather is all business. When she calls back 5 minutes later, her voice is cracking with emotional strain. She knows just how bad I wanted this title because she believed I had it in me. I have sacrificed a lot of time, energy, and money for this goal, but so has she. Even in this moment, we are sharing the heartbreak of a lost dream. I am thankful for the ability to still walk, I am thankful for a partner who is willing to drive an hour to the middle of nowhere to rescue me.

I remember some spectators on a corner and walking another mile to a gray Dodge Caravan sitting with the back hatch stretching open like a cheetah’s jaw. Their eyes look surprised to see me and they ask a couple of times if I’m okay. I am, I think. While I sit there on the back bumper, I go through sharp emotional whiplash and feel like I’m in a fog. The two locals hand me a blanket that ends up smearing with my blood and I feel guilty. They just wanted to enjoy the race, not have to keep an eye on a grown man with a head injury.

After two hours, Heather and I are at the local emergency room and I’m being pampered by late-shift nurses with not a whole lot else happening on their watch. After CT scans and multiple X-rays, I got the all-clear and we left the hospital at 1:30 in the morning to swing through a greasy drive-through. This is a fitting meal when you’re mentally beating yourself up, thinking through all the different possibilities and choices that could have been. The next morning, as we are leaving, we make our way to downtown Emporia just in time for the finish of the XL, a sprint between the German that I met in Spain and last year’s winner, Logan Kasper. 353 miles and it all came down to a few dozen yards. Afterwards, we sneak out of town to head back to my parent’s house, a place that feels familiar and comforting while my entire right side feels like it’s been sledgehammered by John Henry and the cloud of a concussion follows me around. In moments of intense emotion: am I grieving for the race or is this a symptom? In moments of exhaustion: am I tired from the race and subsequent night or is this a symptom? Lines blur and skew and I feel unfocused, but maybe depressed.

A week later, Heather and I made the long drive westward to Oregon spanning over two days. Springdale, Arkansas to Laramie, Wyoming. Laramie to Denio Junction, Nevada. Denio Junction to Klamath Falls, Oregon. 29 hours of driving packed into two and a half days. In the first couple of days of landing, I have a couple of rides and I feel stiff and slow and start to worry the FKT may not go according to plan. I am still nursing twisted knots and green and blue bruises from my wreck in Kansas only 9 days previous. I’m telling myself that I am ready for this FKT attempt and I think I want to believe it so badly because I need redemption from Unbound. If I can smash this record wide open, I am reassured that I have the fitness for Unbound greatness. I’ve made a Google Sheet timetable with a 15 mph average to a bold 18 mph average.

A whole day of laying around and fiddling with my setup and I am set to take off on my quest at midnight. The setup feels dialed. The bike hasn’t felt this smooth since the first ride. Standing outside the building of our Airbnb, the air is a crisp 46 degrees. Cool, but not cold. In the first ten miles, I am warming up and I feel like the FKT doesn’t stand a chance. Over the first hour, though, the temperature drops below 30 degrees, bottoming out at 23 degrees. I had gone over 100 scenarios except for a major temperature drop and was only clothed in my skinsuit and long-fingered gloves. For five hours straight, my body shivered and shook with violent tremors to keep itself warm. Out of the first section, the OC&E rail to trail, I wondered if you can die from hypothermia while still being active. The effort in the dark is a delicate balancing act. I want to go hard enough that I can generate heat, but going too fast means more windchill. I pray for climbs, knowing there isn’t much. Every so often I am in so much physical pain that I just need to stop and catch my breath. Even though the sun is finally over the horizon, I’m ready to bail at mile 110, already feeling like I have ridden 300 miles. My body and mind feel absolutely wrecked. My brain has this fogginess that is an exact replica of how my concussion felt and I worry I’ve agitated a sleeping monster. I continue on, even pulling par with the current FKT’s average speed. As I slog through the infamous silty, red dirt of the Deschutes National Forest roads, I know I’m going to call it. Out of the 363-mile route, there are still 190 miles to go and I am shattered.

Maybe this sounds conceited, but I’m not here for completion. I don’t do efforts like this to check them off a list, collecting routes like Boy Scout badges. I know I’m perfectly capable of finishing the Oregon Outback, but I want the title of Fastest Known Time. Too far off course from that goal and I’m digging a hole and I’ll need serious recovery. To bail now means I can salvage some of my aches and pains and mostly deal with the emotional vacancy of failure. Heather rescues me again from the roadside and we drive down parts of the course towards our preplanned camp spot at the Deschutes River State Park campground. Out of Shaniko, Oregon is a 15-mile stretch of a new chip and seal on a two-lane highway. Piles of tiny gravel undulate perpendicular to the road and the big truck traffic is intense. I imagine myself crawling along the hot highway for an hour being pelted by the flecks of rock that get kicked up under the 65 mph dually tires and part of me is relieved to not finish the Oregon Outback. But, a couple of hours later I’m already scheming to return. I can’t let this business go unfinished.

In bike racing, I have been spurned by many lovers. Cat 4, my first Tulsa Tough, crashed out all three days and ended up on the front page of the Tulsa World newspaper looking like the Invisible Man with all my bandages. Cat 3, Tour of Gila, a junior slid out of a corner while CLIMBING. I had to pull off my own mangled pinky nail in the aid tent after the finish line. It was disgusting. Mid South 24, Velcroed my front tire to a rut at 23 mph, gaining a lovely leopard print of scars running from my right shoulder to my butt. My elbows and knees are layers of scars, like the folding geological formations found on mountainsides. By now, bike racing scars have overtaken my alcohol-induced scars by a long shot. Some racing scars are like those hazy bender scars and I can’t remember where they came from, but I can look at my ugly pinky nail and think “Damn. That kid is riding for Israel Premier Tech now.”

Those scars are markers of love lost, and races interrupted. They also signal to take a few steps back. Days of recovery, shrinking confidence, and the replacement of parts or worse a whole bike. All these steps back to take a bigger look at what is safe, strong, and worthwhile. Walking back from my crash on Dawson’s Hill, I imagine my life filled with a different hobby. Maybe piloting a side-by-side ATV through this rugged terrain, still enjoying this remote landscape, just from the comfort of a roll cage and a gas-powered vehicle. Or perhaps I’m an amateur geologist, picking up random gravel and proposing an approximate chemical makeup. I know that green is more copper-rich, and red is more iron. I’m basically halfway to my new life.

The Buddhists say that all suffering comes from our attachments and our desires. I try not to assign superstitious patterns out of chaos, but this season has been challenging. Last November, I set the 350-mile distance as my main target. The pinnacle of my season would come in early June at the Unbound XL. I would have some good prep running up to the event though: Traka 560km, Rule of Three 200, Unbound XL, and then cap off the 6-week run with a stab at the Oregon Outback FKT. My heart felt so full with this new direction—refocused training, some new events, and a personal touch at Unbound XL. I wanted to be the first Kansan to win the distance. Truth is, I haven’t had a good run at my new target distance. Traka was canceled, Rule of Three was around 13 hours, and I crashed at Unbound XL, and bombed at the Oregon Outback FKT. I put my desire into making this my focus and the reward is a broken helmet, scars, and DNFs. In my center of the universe, everything is conspiring against a clean run. But, you have to have the desire to race at this level, to be this competitive. You have to want it and persistence is the highest form of worship.