PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

Bear with me, this could take awhile.

Epic is such an overused word anymore. It’s hard not to think of it and roll your eyes at its virtual meaninglessness, among hashtags and internet memes and over-exaggeration. Too often, it’s an unearned descriptor. So there is a certain audacity in naming your mountain bike race the Breck Epic – even if it is six days and 240-something miles of gnarly backcountry singletrack, with 40,000 feet climbing and descending, mostly above 10,000 feet in elevation.

But here, in those six days, epic cannot simply be claimed. It must be earned.

The scale and difficulty of the race was not fully sinking in some eleven months earlier, when my buddy Brian and I decided to sign up. We were overdue for a new biking adventure, and somehow stumbled into the intrigue of this one. I’m still not even sure what prompted us to do it. Our uninformed discussions began like all great decisions, “What is it? Can we do? Should we do it? Fck it, let’s do it.”

We didn’t really know what we were getting ourselves into. And that’s part of the fun. One of my favorite lines in literature is from Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, where the aging author rationalizes his daunting adventure ahead. “If the journey should prove too much, it was time to go anyways,” he writes, before he’d even traveled a single mile. That summed up my thoughts leading into the Breck Epic. All or nothing. Breck Epic or bust. I wanted to see if I could do it. Because I didn’t know if I could.

Friday – Two Days Before the Start

After months of training and prep, the days leading up to the race were filled with that great mix of anticipation, fear, excitement, doubt, and just enough unearned confidence to avoid completely freaking out.

We had modest goals for the race. We wanted to finish, have fun, and make a good showing. Brian was primarily worried about the altitude, and getting over the long climbs. He is a Cat 2 mountain bike racer and really strong rider, but he was also coming out here from Indiana, where he lives about 9,000 feet below where our hotel would be for race week. My main concern was dealing with technical terrain, particularly on descents. I live in Colorado and have been biking for some 30 years, but I was coming into Breck very new to singletrack riding. It would be my 3rd ever mountain bike race.

Brian rolled into Colorado five days before the start, to acclimate a little to the altitude – first stopping in Denver and riding in the foothills before we headed up to Summit County a couple days before the race.

We were fortunate to be staying at the Beaver Run resort, which served as the race headquarters for the whole week. We had a convenient set up in a condo with plenty of room for ourselves, bikes, and gear. A unique aspect of the Breck Epic is that you get the full stage race experience – a first for me – without changing location each night, since each stage starts and finishes near town.

When we arrived on Friday, we mapped out a short pre-race loop for the afternoon. But our ride got cut short after Brian flatted with a nasty gash in his sidewall, at which point rain and storm clouds rolled in and the temps dropped. So we shot back to down to town, tinkered with our bikes more, and grabbed some dinner.

“I don’t know how we’ll do in the race, but in eating, we’re going to put on a clinic,” Brian concluded.

Saturday – One Day Before the Start

Saturday was check-in day, with registration and the first daily riders’ meeting. If I thought the stoke was high before, Saturday was a whole different level. It was palpable. The 400 or so riders hanging around race headquarters were the fittest group I’d ever seen, hard men and women who were ready to intentionally suffer for the next week. And psyched about it.

Each rider meeting consisted of comments from the race director, Mike McCormack, descriptions of the next day’s course, and an open Q&A. The meetings were part tutorial and part group therapy – and oddly comforting, knowing that you were not in this alone and that everybody would be suffering together. Also, Saturday’s meeting had a cash bar, which was dope.

The Breck Epic’s origins come from MikeMac and his crew and their desire to showcase the incredible big mountain singletrack that is available in Summit County, rides that few people get to experience. But they aspired to do so in a way that avoids the pretense of most big events, where licensing and rulebooks and other funless aspects suck the joy out of it. Mike’s casual, off-the-cuff style succeeds in injecting the race with a bit more humanity and a bit more humility than you often see at these things.

The tone that Mike and his team set for the race strikes the right balance between the significance of what we’re doing and the fact that it’s still just riding bikes in a cool place. We’re not curing cancer or solving world hunger, as he said. So we shouldn’t take this too seriously, nor too lightly either. It’s the kind of expectation-setting that makes you want to show up, ride hard, be cool to one another, and appreciate the experience for what it is.

There are three rules at the Breck Epic, and three rules only. Coming off the last couple years of racing triathlons and more regulated cycling events, where there are far, far too many rules to keep track of, this was welcome relief. Simple is good, simple is clear.

- Don’t be a dick. 2. Don’t litter. 3. Wear your helmet.

It was cool to see such a massive, sprawling event imbue its participants with such a high level of trust and empower us with self-policing. As we were repeatedly told, just be cool to each other. When there were reports of wrong-doing (i.e. littering, nature breaks right next to feed stations, etc.), racers were simply told to cut it out, and if you didn’t, you were gone.

“The course is good. The course is hard. The course does not let you hide,” MikeMac concluded at the pre-race meeting. It was equal parts exhilarating and terrifying. There would be no hiding. You have to earn it.

The rest of Saturday was spent waiting and pacing and nervously scanning the course map. We tried to kill time by needlessly tinkering with our bikes, while Brian waited for a wheel issue to get fixed.

We ate pasta and chicken at the Breckenridge Brewery, then sat outside the bike shop waiting for Brian’s wheel to be ready, watching the sun sink below a 12,500 foot mountain ridge that we’d be riding over a few days.

Normally I can’t sleep at all the night before a race. My monkey brain usually just won’t shut off. But Saturday night, I slept like a stone.

SUNDAY – STAGE 1: Pennsylvania Creek, 35 miles, 5,500 feet

We woke up Sunday morning with what felt like fire in our blood. Nerves and excitement made for squirrely stomachs and sweaty palms. Words escaped us, replaced by nods of self-encouragement and deep breaths. Coffee was poured. Breakfast burritos were eaten. Aid bags were packed. There was nothing left to do but go ride bikes.

For the beginning of such an insane event, the start corral was remarkably calm and casual. Riders greeted each other with easy smiles and handshakes and good lucks. Friends and teammates gathered. Pictures were snapped. Bikes were gawked at.

Brian and I were about midway back in the corral. I saw Stephen at the start, who joined us, as well as Chris Magnotta, who I had not met before. They both were doing the Epicurious version of the race through the first three stages, ultimately finishing in the top 20 of a stacked men’s open category. The familiar faces helped stave off the mounting nervousness that came in the form of stomach bile. This was happening.

As the countdown to the start ticked away, the escalating chant of AC/DC’s Thunderstruck piped through the speakers. The gun went off. And everything was blank.

I don’t remember anything for the first few miles. I know we climbed up some paved road, then hit some dirt, at which point I realized I had started too far up front. Brian was already long gone, up ahead somewhere, as he would be every stage. Through the first sections of singletrack I was riding well, but uneasy with the jammed, wheel-to-wheel traffic. I held my own though and was just trying to ride smooth and steady until things thinned out.

Stage 1 is a jagged, rocky, wheel-eater of a course. It was up and down all day, mostly over loose, sharp, rock-strewn trails. After navigating the crowded early sections, I rode away from a slower group on a long doubletrack climb, and caught up with another group that I rode with the rest of the day. That became a trend, where I would typically catch or pass people on climbs, only to lose massive ground on descents or technical sections where I often struggled.

I was feeling good about the first day, until around mile 30, when stupid hit. At a sharp, downhill left turn off singletrack onto a rocky jeep road, I lost too much momentum, and my front wheel dug in, which launched me over the bars, onto my left shoulder. I folded into the ground like a napkin. My body, bike, bottles, sunglasses, dignity…all strewn across the dirt. The course marshal at that corner ran over to offer assistance. He thought I’d broken my clavicle or busted my shoulder the way I fell. Once I dusted myself off and took inventory of limbs and bones and spirit, I deduced that my left ribs took the brunt of the hit. Bruised but not broken. Pierced, but not dead.

I limped to the finish line, where Brian greeted me. We were both shelled, but happy to be done. Back at Beaver Run, we snacked at the recovery station, had the most delicious ice cold Coca-Cola that has ever touched these lips, washed our bikes, grabbed lunch, and ate handfuls of Advil.

The rider meeting included podium awards after each stage. Awards were time-consuming, but also terrific recognition to the fast folks at the front of the race and a cool thing to do for all the categories.

After the meeting, we snagged turkey/bacon/avocado paninis for dinner, tuned up the bikes, and hit the rack.

“Five more days, huh?” Brian asked.

MONDAY – STAGE 2: Colorado Trail, 37 miles, 5,200 feet

The bruised ribs from my Stage 1 crash made for difficult sleep. I woke up tired and stiff, but ready to go. My breathing was mildly labored, but nothing that would prevent me from riding.

It was interesting how quickly our morning routine was established. We’d wake up around 6am. Make coffee. Eat breakfast. Pack up our aid bags and go drop them off at the race tent downstairs. Come back to the condo, kit up, and head to the start before 8:30am.

The aid bag system is another fantastic feature of the Breck Epic. Each rider gets a set of numbered aid bags correlating with your race plate. It’s like flat rate shipping boxes, as MikeMac said – you can put whatever you want in it that you might need during the race. You drop them off in the morning, and volunteers shuttle them to each aid station. My bags included a fresh bottle of Skratch Labs hydration mix, extra TrailNuggets, energy chews, extra tube and tire, spare cartridge, and rain gear. And the volunteers were terrific in helping you get what you needed at each feed station.

Stage 2 is singletrack mecca, if you’re into that sort of thing. We went up over Heinous Hill, which is a steep climb that included some pushing. Then down a steep, burly descent on Summit Gulch Road that was as fun as it is terrifying. I felt good on day two, but struggled on Galena Ditch, a singletrack section that had steep drop-offs on either side. It’s a really cool trail, but the drop-offs spooked me and slowed me down a lot, so I lost contact with my group. The climb up North Fork to West Ridge on the Colorado Trail was tough, but a good grind. I had ridden this section in the Breck 32, and was able to clean a lot more of it this time around. A volunteer at the preceding aid station asked me if I wanted my rain jacket. I checked the skies, and said, nah. Foreshadowing.

Of course, when we topped out on the ridge at the high point of the ride on the Colorado Trail, hail began to fall, hard. More like the skies were throwing it at us. Just as we were going to descend some very fast mountainside trail. Visibility was virtually zero, and the trail itself was masked by hail and water. But there was no place to go but down, and nothing to do but trust yourself and your bike.

It was a crazy, fun, fast, and freezing descent. And I made it down and finished in one piece. Brian finished a ways ahead of me, we met back up at the condo for the afternoon routine. Eat. Drink. Riders meeting. Dinner. Sleep.

TUESDAY – STAGE 3: Mt. Guyot, 36 miles, 6,500 feet

Sometime towards the end of the second day and the beginning of the third, you start to get numb to the routine. All you see when you close your eyes is trail and trees and rocks and roots. Energy sinks. You go through the motions before and after each stage, checking mental boxes along the way. Eat. Drink. Sleep. Bike. Repeat. The only thing that breaks the monotony is the actual riding.

I have never done a stage race, so I wasn’t totally sure what to expect in terms of how I’d feel each day. I had high hopes that I would recover well, day to day. And maybe even get stronger relative to other riders through the week. But it was around Tuesday morning when I realized that this would simply be a race of attrition and a matter of whether or not I could actually finish.

Tuesday greeted me with stomach issues in the morning. It was doing “fancy things” as a friend of mine likes to say. Without digesting breakfast that well, I ended up feeling bonky all day. And it was not the day for it.

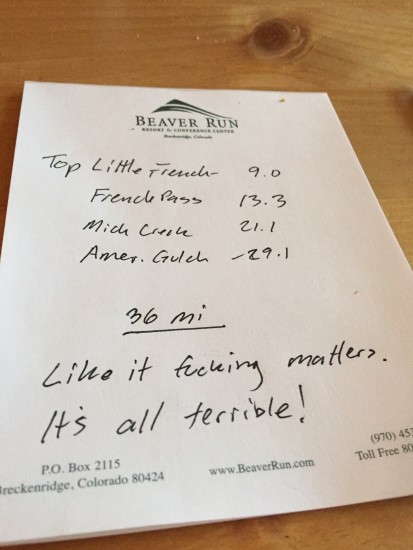

The Stage 3 route took us up Side Door, down the rocky Little French, up and over French Pass, around Mt. Guyot, back up to the Colorado Trail, down again on a really technical descent, and then up the grueling American Gulch climb. We crossed the Continental Divide. Twice. Peaked out at 12,500 feet, and endured some of the toughest, rockiest descents that I’d seen.

The altitude took its toll on me, as did the long hike-a-bike section atop French Pass and punishing descents. It felt like the course was specifically designed to expose my weaknesses as a mountain biker.

Late in the stage, after riding through more rain, I started going to a dark, doubtful place in my head. I rode alone without anyone else in sight most of the rest of the way, struggling with every pedal stroke. I was frustrated, and felt like I wouldn’t finish the stage, let alone the whole race. Part of me didn’t want to either. There’s nothing worse in a moment like that than indifference. In my head, I was on the brink of quitting. I was not going to finish.

On the final merciless climb up American Gulch, I caught a rider who I think was with the Costa Rican crew. He was bent over his bike and had just vomited. He said he was ok, but struggling with the altitude and couldn’t catch his breath. It was just the two of us on this stretch, and I didn’t want to leave him like that. So I stayed with him until the top of the climb and the ensuing descent. I was glad he was ok, and it was strangely a welcome distraction from my own thoughts.

When I finally reached the end of the stage, I stood at the recovery tent, staring vacantly at the ground, empty and decimated. One of the many wonderful volunteers offered to make me a bacon pickle sandwich. It’s called the Dominic, she said. It was restorative, and it was glorious.

Brian and I met back up and traded stories on the day. He finished well ahead of me again, but also struggled. As did many others. And there was some comfort found in that. The Breck Epic is easy for no one. It doesn’t matter if you’re a pro on the podium or a six hour guy. This will hurt, period. You just have to keep going.

WEDNESDAY – STAGE 4: Aqueduct, 42 miles, 7,000 feet

On day four, the longest stage in terms of mileage, I woke up feeling like I had a sudden onset of full body arthritis. Everything hurt. Until I cooked up some bacon to add to our morning fuel. It was exactly what I needed.

Though the early climbs were tough and steep, I felt good once we got going. It was the first day that I didn’t notice my rib hurting and that I felt like I could breath right. The first part of the stage was a lot of up and down, with some deliriously fun, wooded singletrack.

We hit Vomit Hill, which I grossly miscalculated. There was a small group of people cheering and clanging cowbells at the bottom, which got me all fired me up. Thinking it was shorter than it was, I hit the bottom hard and almost blew myself up. I eventually spun out and had to push much of the rest of the way. After that it was more fun singletrack on down the valley towards Keystone.

The Keystone Gulch climb back up to the Colorado Trail is a long grind, I think five or six miles of up. But I felt strong the whole way, catching and passing some other riders.

And then it happened. When everything is just in its right place.

The descent down the Colorado Trail was the smoothest I’ve ever been on a mountain bike. It was I think the first descent where nobody passed me. I joked later with Brian that it was the equivalent of when Keanu Reeves finally sees the Matrix and starts stopping bullets in mid air with his mind. That’s what it felt like. I didn’t put a foot down from the second feed station at the bottom of Keystone Gulch Road until the bottom of the Colorado Trail descent. Nothing hurt that entire time, not my legs, not my lungs, not my ribs, not my hands or back or shoulders. Everything just clicked. I was stopping bullets with my mind.

I did labor a bit up the last climb on Summit Gulch, but it didn’t matter. This was the day I needed. All the w00ts were had. You tend to ride with and finish with a lot of the same people throughout the week. At the Stage 4 finish though, there were no familiar faces. I’d come in with a whole new group.

When I rejoined Brian later, we were all smiles. As bad as Stage 3 went, this was good. It was the day when we got back to just riding bikes. It was the day when I finally knew that I could finish this thing.

THURSDAY – STAGE 5: Wheeler Pass, 28 miles, 5,200 feet

There’s not much to say about the Wheeler Pass stage. It is long, it is hard, and it is brutal. Aside from the views from the top, there is not much enjoyable about it, other than to say you have done it.

The course starts up the rocky, and sneaky technical Burro Trail, and proceeds into an unending slog up the Wheeler Trail, which tops out well over 12,000 feet, along the mountain ridge separating Breckenridge and Copper Mountain. The top part is so steep and rocky that it turns into a long march of people pushing their bikes – “very expensive water bottle holders” as one guy said to me.

The hike-a-bike was interminable. I just kept trying to put one foot in front of the other. There’s a song called Coffee by Sylvan Esso, where the chorus goes, “Get up/get down, get up/get down…” I kept humming that to myself in my head for much of the long grind up Wheeler. Get up. Get down.

I knew I could do it. But I was concerned about getting down before any weather-related time cutoffs were implemented. There were no hard limits, but we were told that if weather approached or if it got too late in the day, they would pull people from the course. So we didn’t die.

The Wheeler course was different this year. Instead of dropping all the way down to Copper Mountain, on the other side of Wheeler, we dropped down some narrow, exposed singletrack for a mile or two before heading back up Miner’s Creek Trail to again summit the ridge. Maybe it was the altitude that made me punchy or maybe it was the exposed thousand foot drop to my left, but I really struggled above tree line. Much of it was not rideable for me, but even the stuff I could ride was tough. That kind of terrain makes a small rock look like a Sprinter van.

Once we made our way back over to the Breckenridge side, it did not get any easier.It was jarring to be on a bike, well above Breckenridge’s highest chairlift. Though the climbing was done, the trail was still periodically unrideable for someone at my skill level. So I pushed and hiked and clawed my way down, until I could let it ride.

After I made it past the second aid station at the bottom of Miners Creek trail, I felt better about making any time cut. But there was still riding to be done. I didn’t realize until later that I had dropped off my empty bottle in the aid bag without picking up a fresh full one.

Near the third aid station, two moose blocked the course. Volunteers helped verbally guide me around them, as I bushwacked through the woods with my bike over the shoulder.

The last climb through the ski area felt like it would never end. I recognized some of the ski runs and thought about just bombing down them to the base and a beer and a bed. But I made it to the finish.

Brian and I were completely destroyed after Stage 5, but also delirious with relief that we’d made it this far. Stage 6 was the easiest of the bunch, and barring catastrophe, it felt like it would be a victory lap, even if, like me, you were hours off the back.

We celebrated getting this far with burgers and beers at Breckenridge Brewery, along with Mike, another rider from Indiana, knowing that we’d made it through the toughest part.

FRIDAY – STAGE 6 : Gold Dust, 30 miles, 3,600 feet

The final stage of the Breck Epic is a fun one. It starts with punchy, steep singletrack climbs, before taking us over Boreas Pass, down some fun descents, through what can only be described as a dirt bobsled track, and then finishing with a climb back over Boreas Pass and down Gold Dust to the finish.

It was fun from the start to finish. I struggled on the first climb, as I had each day. But once I got through that I felt great. Through most of the course, you could hear other riders hooting and hollering, yelps of joy that we get to ride bikes over mountains and through the woods in such a spectacular place.

On the final big climb, I went hard for no other reason than I could. In the 210th mile or so of the week, my legs still felt good on the final ascent over Boreas Pass – a testament to the miles put in this year. At the summit, I took a beer hand up and downed it. I looked around, said thank you to the volunteers, and soaked in the sights and sounds and smells for one last moment. It was glorious.

The descent back down was fast and flowy fun almost all the way to the finish line, where Brian and many other finishers were waiting around, high-fiving, congratulating one another, not wanting whatever this high was to wear off.

We spent the afternoon eating chips, drinking High Life, and basking in what we’d just accomplished. The awards banquet was a great acknowledgement for the top-placing riders in each category. The best part was MikeMac’s recognition of race staff and volunteers, calling them up onto stage for a standing ovation.

Later, we celebrated with other riders at Stage 7 – the after-party at the Gold Pan Saloon. It was cool to see pros and top finishers celebrating with the age-groupers. There were shots of tequila. There were glasses of whiskey. There was dancing and debauchery, hugs and high-fives. We’d earned it. All of us did.

EPILOGUE

All told, I spent 34 hours riding my mountain bike in the Breck Epic. I finished second to last in my age group, in which 50 out of 58 riders finished all six days. Brian finished 40th, with a total time of just under 28 hours, an incredible performance for a lowlander.

According to the questionable accuracies of Strava, I covered a total of 214 miles, and climbed about 35,494 feet in those six stages. To fuel all that, I went through two large bags of Skratch Hydration Mix plus another dozen single packs. I ate twenty-one TrailNuggets, a dozen bags of energy chews and packets of Untapped Maple Syrup. I had three Dominic sandwiches, a dozen eggs, a half dozen bananas, eight bagels, two large bags of granola, four chicken sandwiches, more than a pound of bacon, three paninis, six finish line Cokes, one pizza, baked ziti, two large bags of a pretzels, two large bags of chips, one basket of fries, and a 50/50 beef/bacon burger.

It’s hard to adequately describe the experience of going through something so intense for so long – the unbelievable highs and lows, the numbing routine, the suffering, the uncontainable joy, the incredible sense of accomplishment. It’s made for difficult re-entry.

In piecing together my jumbled thoughts for this write-up, I struggled to find any coherent narrative. But I relished in thinking back on all the moments that shape such an incredible experience.

The seemingly laughable claim that Brian made in the pre-race riders meeting that “we should do this race every year.”

The jingle from the hotel arcade machine that echoed in the hallway each morning en route to drop our aid bags off, which reminded me of a song in a short film that made me miss my soon-to-be wife and two dogs. Every morning.

The persistent refrain of “You are here, you are doing this” that I told myself repeatedly through each stage, to stay present and focused.

The quiet encouragement offered to Brian, when he was wrought with doubt about getting over some of the climbs, and I knew he would crush it.

The surrender to the elements and to gravity when it’s hailing and raining and you can’t even see the six-inch-wide trail you’re flying down on the side of a mountain.

The relief and gratitude I felt after Stage 5, when I said to Brian, “I wasn’t sure if I’d make it.” And he said, “I was. You’re all heart, always have been.”

The guy who yelled out “you’re a damn billy goat” when I cleaned parts of a steep, rocky section of double track where everyone else around me was pushing.

The bike club that was riding in honor of their teammate who died of ALS last year and whose wife had also recently passed away.

The conversation I had with Mark McKinnon about politics while we negotiated a perilous section of the Wheeler descent. Yeah, that Mark McKinnon. He can shred.

The freakish sight of seeing a tandem – a tandem! – ride this course. I still don’t understand how that’s possible.

The woman who raced and finished, who has MS, and the many riders in their 50s and 60s who were out there absolutely killing it.

The total badassery of all the single speeders, who you definitely want on your side in a bar fight, and who you maybe should not make direct eye contact with.

The point late in the Wheeler Pass stage when I screamed to myself, alone, frustrated, somewhere in the woods, just below tree line, “When will this fcking be over!?”

The impossible odds that neither of us had any flats or mechanical problems during the race, a serious testament to Brian’s Niner hardtail, my Yeti ASR, and wonderful dumb luck.

The man named Rolf who crashed near the top of Wheeler Pass, bloodying his face, but braving it out to finish the stage and complete the full six days, with a warm smile on hard days.

The hoots and hollers you’d hear in the woods, or along a ridgeline, that signaled the complete unbound happiness of hitting a groove, of shedding any suffering or hurt, and just riding bikes with cool people in an amazing place.

The many, many gracious staff and volunteers who make the Breck Epic one of the best run events I’ve ever seen. Without exception, staff and volunteers were kind and patient and supportive and encouraging. The course crews – the markers and the sweepers – do an incredible job every day, as the first ones out there and the last ones to leave. And often times, late in a stage, deep in the pain cave, it was an aid station volunteer or course marshal who’d been at it for six or seven or eight hours who helped give you that one last final last push you needed to get to the finish.

The many, many miles that got me here, the time it took away with my fiance and friends and grownup responsibilities, and all the encouragement and support of friends and family and teammates and strangers alike.

And lastly, the total pride and appreciation that I got to do this, endure it, and share it with one of my best friends, without whom I probably would not have made it.

The Breck Epic was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. It tested me in every way. It made me a better rider. It made me tougher rider. It was a completely humbling experience, both in the level of competition and in the terrain. It made me all the more grateful for the chance to go ride bikes in a special part of the world. And it made me better appreciate an experience like this.

Because we couldn’t just claim it was epic, we had to earn it.

No comment yet, add your voice below!