I stared up the rusty colored scree field and strained to make out the solitary post just barely peaking above the ridge line that topped it. That was the prize. That was the summit of Imogene pass, the second summit of the day, the crux of the ride. The post was not far as the crow flies, maybe only a couple hundred feet away. It felt much further, infinitely far all things considered. Our progress was painstakingly slow. The fatigue and altitude had quietly stolen away all of our spit and venom all day long leaving us with dry mouths and heavy legs. The 4×4 road surface was generously strewn with wet, coarse rock. We shuffled on our feet.

I swiveled left nervously, my eyes following the ridge line west until they found their target about a mile away. A dark wall of clouds was quickly approaching us. Only ten minutes earlier they had seemed twice as far away. The clouds didn’t move if you stared at them but if you turned away they darted closer at an astonishing pace. Now they were nearly on top of us, thumb and index finger shaped like an O, ready to flick us off the mountain.

A quick mental calculus painted an obvious picture: We weren’t going to make it. We were only a half mile from the summit, a distance that we could cover in a few minutes on a normal ride, but at 12,600 feet with steep gradients ahead of us it would take us more than fifteen minutes to cover the ground.

“What do you think?” I asked Peder, hoping he would contradict what I knew to be true.

“It’s going to hit us.” he said. So much for that. “But I really don’t want to high tail it back down to Telluride.”

A strong gust of wind hit us, a light rain along with it. If we turned around now we would fail to complete our planned loop but if we went for the summit we’d get t-boned by the storm; completely exposed on a ridgeline at 13,114 feet.

—————

“You’re going back already?”

That was the cold response that I received from my wife Sarah when I told her that I wanted to go back to Ouray, Colorado in September. Only a couple of weeks had passed since I had gone for the first time, but I hadn’t stopped thinking about how to get back since I left. Even as I planned it I knew it would be a challenge, and also a bit of a strain on my family.

Ouray was in my head. I had touched the live wire. A light bulb lit up. A fuse popped and after one visit I now found myself completely rewired. Discovering the San Juan mountain range with it’s dominating peaks, threatening beauty, and spider web of mining roads was like discovering a fresh reason to ride bikes, a new way to evolve as a cyclist. It left me with a Feeling of wanderlust and a nagging need to sit on the side of a high alpine pass, staring out into views so beautiful that my mind couldn’t properly process them.

So yes, I was going back already. I gently, tenuously explained to my wife that I needed to go back one more time before the snow started falling again. Colorado’s highest mountain passes are only clear of snow for two to three months of the year. With a single big September snow they could close again through the following June or July. One trip to Ouray had been incredible, but I needed one more trip in order to stash away enough of That Feeling to get me through the winter. Sarah was skeptical. Sarah has been shockingly, amazingly supportive of Rodeo since I started it in 2014, but the quickest way for me to give her cause to withdraw support is to get tunnel vision; to go bike-crazy and leave behind her, the kids, and our family’s collective sense of purpose and adventure in the process.

High mountains can be as much of a mistress as any other thing if you let them. You can spend days, weeks exploring them. You day dream about them. You plan ways to get back to them. They take you away from other things that you love.

I can’t dispense any advice on how to have a passion for something and keep it in check before it erodes relationships with far more importance and value, but I do have Sarah, and she keeps me honest.

Sarah green lit my return to Ouray, but not before holding my feet to the fire.

——–

I sent out a flare to the Rodeo team asking if anyone else could take some midweek time off work and head back out to the hills with me. Peder was the only one to respond that he was able. Peder started Rodeo with me on day one in 2014, so I couldn’t think of a better person to go with. He and I ride at identical levels and enjoy that friendly aw-shucks sort of competitiveness that pushes us to do things that we’d never attempt on our own.

We formed a plan. This trip would be short and ambitious with a late Tuesday PM departure, arriving in Ouray near midnight. Wednesday day we’d attempt a challenging alpine loop and bag some of That Feeling. On Thursday we’d tag on a smaller ride before packing up and returning to Denver. 48 hours was all that we could muster but we’d make those hours count!

—————

On the first trip to Ouray we’d ridden Imogene pass and the Alpine Loop. Both were easily top five rides of my life. I remember Jered buying a guide book on the trip and turning page after page of impossibly gnarly, impossibly scenic passes that we could attempt. In the guide book one pass seemed to stand head and shoulders above the rest: Black Bear. When I had plotted my route up Imogene I had briefly considered Black Bear instead, but there was’t much information available online about cycling conditions over that “road”. The information I did find suggested that Black Bear is widely considered to be the most dangerous 4×4 road in Colorado. I did not find that encouraging at the time.

If you Google “black bear pass” you are much more likely to find 4×4 or motorcycle information than bike information. Click on the image search tab and you’ll be greeted by an extensive gallery of morbid photos of vehicles that have mis-judged the infamous technical rock steps on the route and tumbled down the ravine below them. People have died on Black Bear Pass, and it seems to happen with enough regularity that the sheriff sometimes considers closing the route entirely. Thankfully as of this writing it is still open, and I’m glad that it is because an extremely challenging and dangerous 4×4 road is still most likely navigable by bike and even if you can’t ride it all there is always the option of getting off and walking.

The lack of cycling intel non withstanding I couldn’t get Black Bear out of my head. The idea of riding a wild jeep trail of a road that eats vehicles for lunch and tops out just under 13,000ft (4,000m) is irresistible to me. A quick check on Strava revealed that at least 33 other people had ridden it, so how bad could it be?

I discussed with Peder. Once again he was totally game for the idea. We had one problem though: We both hate out and back rides. We needed to make a loop. If we started in Ouray and road up Red Mountain Pass to Black Bear we could summit the pass then drop down to Telluride. That much would be easy. But how to get back to Ouray? The simple option was to head back out on the road and loop back around through Ridgeway, but that would end up being a highway ride. So boring! We hadn’t come here for road riding, we had come here for That Feeling, and you can only get That Feeling up high.

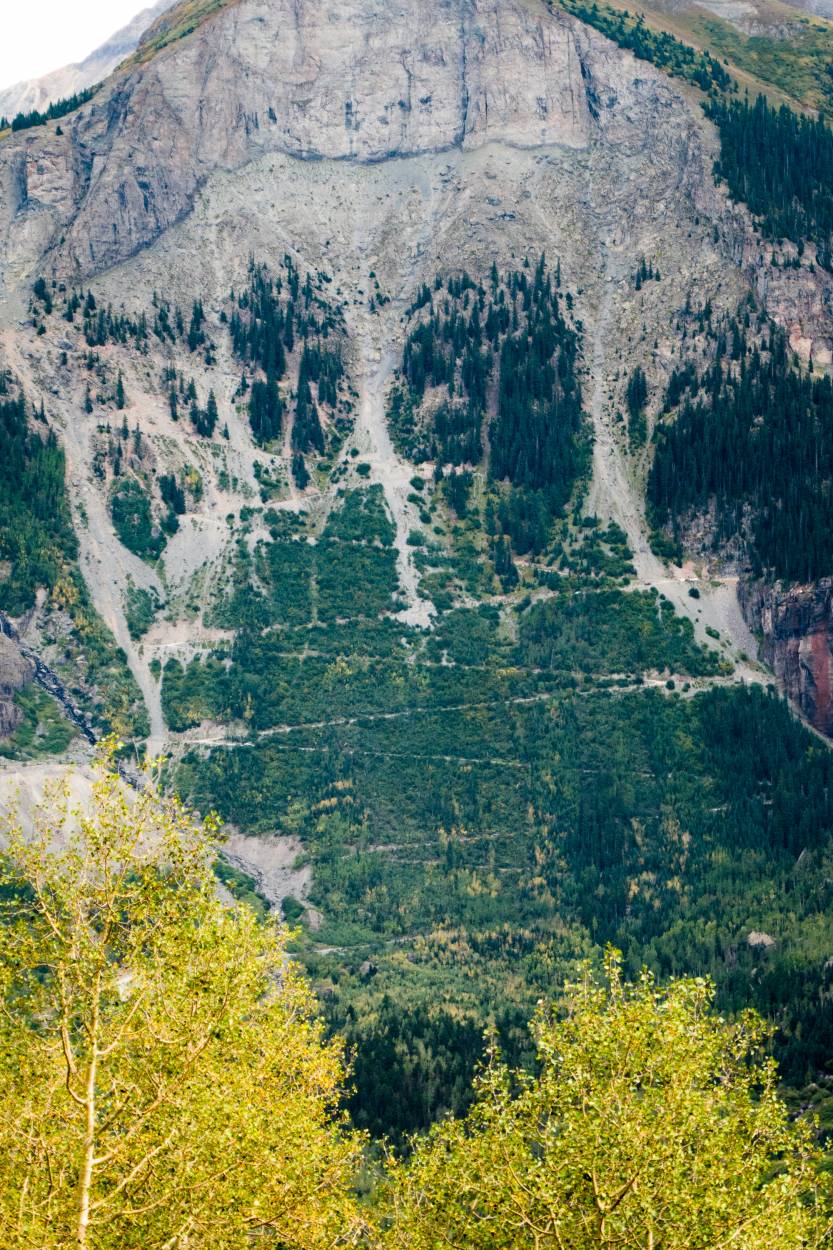

The other option then was to return to Ouray over Imogene pass. This idea seemed a bit eye watering to me. I’d ridden Imogene from Ouray and it was easily the most ridiculous climbing I’d ever done on a bike, but I hadn’t ridden the other side of the pass from Telluride. I sent a quick note to Jered to ask his opinion of the road because he had driven it in a Jeep on our previous visit. I remember watching him and the rest of the crew in the Jeep crawling down the road from the pass towards Telluride and being 100% sure that they were going to lose control of the vehicle and die. They made it though, which made me believe him when he said that route conditions MIGHT be more reasonable to ride than the Ouray side. He said to go for it.

With that in mind Peder and I had a route. We would begin with roughly 17.6 miles of virtually non stop climbing from Ouray, up the Million Dollar Highway to Red Mountain Pass, then up Black Bear pass. Total elevation gain: Roughly 5,000 feet.

We would then descend from Black Bear to Telluride, slam down a solid lunch, and begin climbing directly out of town towards the summit of Imogene pass. That is roughly 4,200 feet of additional climbing in 8 miles. With a good lunch all things are possible.

Generally speaking you know you’ve had a big day of climbing if you ascend 1,000 feet or more in 10 miles. That seems to be some sort of golden 100:1 ratio. Our route had us climbing just under 10,000 total feet of climbing in 42 miles with half of those miles being descending. That’s closer to a 100:4 ratio. Translation: This route would be, for both of us, an insanely difficult punch in the gut.

When waking up on the morning of a ride like this you are greeted with a huge mix of emotions. Excitement is undeniably at the top of the list. Something awesome is about to happen. You can feel it. If you are riding with someone else they feel it to0 and both of you know it. The combined effect is a hotel room charged with a giddy sense of expectation. Backpacks are filled, chains are lubed, brakes are checked, and breakfast is smashed into stomachs that are simultaneously contracting due to nerves.

Just under that excitement lurks another feeling: Fear. Rides like this are a little bit, maybe even a lot of bit dumb. The sense of unknown is overpowering. There are no guide books telling you that success is imminent because nobody writes guide books about rides like this. The sense of doubt that you are making any sort of good decision is always just on the edge of your mind.

On this particular day the weather forecast predicted a strong chance of afternoon showers. Afternoon showers at 13,000 feet are a thing to be avoided. Lightning is a distinct possibility. About fifteen people die each year in Colorado from lightning strikes. When standing on a naked mountain strewn with nothing but rock a human becomes the lightning rod in the event of an afternoon storm. Afternoon showers at 13,000 feet in September could also mean snow, or at the very least sleet. Snow + Sleet + Lightning + 100% exposure with nowhere to hide = Fear.

So yes, I think we were both a little bit scared. The idea of bailing on the route presented itself strongly, at least to me, but Peder and I resisted. It’s so immensely difficult for us to carve out time to take bike a trip together. We only get one or two opportunities per year like this. We knew that we weren’t going to make it back to Ouray for another year. We also knew how to prepare for weather. We wagered that on this terrain with these gradients we could simply turn around and descend thousands of vertical feet in mere minutes if the proverbial shit hit the fan. Yes, the forecast called for a possibility of PM showers but it also left just enough room that safe passage could be a reasonably expected outcome. Sometimes you have to abort out of caution and sometimes you have to go for it. We decided to go for it.

—————

We started our ride to beautiful conditions on the Main Street of Ouray. Mostly blue skies shown overhead with just a few scattered clouds. We pointed our bikes up highway 550 out of Ouray which is otherwise named the Million Dollar Highway.

Wikepedia reveals several interesting bits of information about the Million Dollar Highway:

The origin of the name Million Dollar Highway is disputed. There are several legends, though, including that it cost a million dollars a mile to build in the 1920s, and that its fill dirt contains a million dollars in gold ore.[3]

There are seventy named avalanche paths that intersect Highway 550 in the 23 miles between Ouray and Silverton, Colorado

It is sometimes said to be safer to drive the Million Dollar Highway in the winter because the champagne-powder that covers it has more than once cushioned the fall of vehicles who’ve driven over the side of it’s precipices.

Speaking from personal experience the one fact that I know to be true about The Million Dollar Highway is that it is absolutely breathtaking to ride on a bike. The road is very narrow and winds up a dramatic gorge with steep cliffs. The pavement is almost immaculate and it’s a good thing that it is because the distinct lack of guard rails (which aids in the removal of 300 inches of snow per year) would otherwise make riding it feel incredibly treacherous.

The toll the road takes on drivers sounds strikingly similar to that of Black Bear Pass, but one would think that somehow the road would be safer given that it is so beautifully maintained.

Between 2005 and 2015, she said, there have been 412 accidents between mile marker 52 (at the base of Coal Bank Pass) and mile marker 92 at Ouray. Sixty-six accidents involved injuries, and eight brought fatalities. – Source: Telluride News

I’m not sure why I keep returning to the theme of vehicles plunging to their deaths in this Journal entry, but the cause may have links to primal memories that I have of my dad speeding down logging roads in the family VW Bus and scaring me to death when I was a kid. It is also true that my parents drove The Million Dollar Highway in said VW Bus before I was born. Coincidence? Maybe riding bikes on similarly treacherous roads in my adulthood, this time with my fate squarely in my own control is some sort of way of exorcising my own demons.

—————

Peder and I made great progress up the highway. That euphoric sense of finally getting moving accompanied us in the early miles. The climb up 550 is pretty much a non-stop climb but you don’t think much about the effort as you do it, the views are far too distracting for that. To the left, to the right, up and down. Every where we looked the San Juans were on full display. Each new turn revealed fresh vistas. The obvious fact that Peder and I were both gawking at the same sights didn’t stop us from constantly saying “look at that” to each other.

The lateness of the year meant that the aspen had started to turn on the higher slopes of the canyon walls above us, just before trees ended entirely and only the high rocky peaks continued on.

“This bike is great!” said Peder. He was talking about the Donkey that I had lent him for the trip. I smiled, not because Peder liked it, but because this was his first ever ride on a Traildonkey. Peder has reached that enviable point in his life where he has so many amazing bikes that it really, finally doesn’t make sense to add yet another one to the stable. Sacrilege? Maybe. But its true.

On a ride like we were on there really isn’t any one perfect bike to ride. If you want the most comfort you would definitely want to do it on a mountain bike with at least front suspension. But why would anyone interested in comfort ever do a ride like we were on? The ride was much more about embracing discomfort than it was much else.

Or was it?

What was the point of today’s ride? I wondered to myself. Everest pioneer George Mallory won for having the best answer ever when he said “Because it’s there”. But was that our reason? I don’t think that it was. I think Peder and I were there for other reasons. Yes we wanted an endeavor with which to challenge ourselves, we wanted to set a goal that we didn’t have a guarantee that we could complete. We wanted the rewards of high mountain views that not many people ever get to see. We wanted to do it all under our own power. But more than that I think trips like this, undertaken as a team, are blank canvases for developing friendships. With so much of our culture moving online these days I’m often numbed to the fact that real friendship does not happen online. There is no subtext to an online “like”, no depth at all. Endless thumb scrolling does not challenge us or sharpen our character. As kids “mature” into adults friendships become more and more difficult to form. Discretionary slow time that it takes to develop a friendship becomes rarefied not only because we naturally have less of it but also because we cease to prioritize it. In a culture obsessed with chasing luxury, it seems ironic that building friendships is often a luxury that we do not afford ourselves.

550 plateaus a bit at Crystal Lake, about 6.5 miles up. Do not be fooled as we were that you’ve summited Red Mountain or arrived at the Black Bear turnoff. There are another seven miles to go. Do enjoy those seven gradual miles of climbing though, because once you hit Black Bear Pass any hints of gradual climbing become a thing of the past.

We paused at the Black Bear turnoff to down some food and exhale. So far so good. The skies were still blue and temperatures were perfect for climbing. It’s a funny thing to ride a road that you’ve heard so much about. Would it live up to expectations? Could it really be that bad? Was the day about to become utterly miserable? Within a matter of a few hundred feet some of the answers to that question became obvious as we hit our first 20+ percent gradient. We’d brought some pretty serious gearing on the ride: 1x setups with 34t in the front and 10-42s in the rear. I thought that gearing would last a bit, like maybe we could save the 42 until things got really truly ugly. But no, a few hundred feet up the road I had dumped all the way to my granny looked back at my non-remaining gears, and said “that’s it?”. This was going to be a long day.

Black bear is a bit of a staircase of a climb. Here and there it mellows out for brief stretches. This allows you to catch your breath almost. Then it dumps a 25% gradient on you and laughs at you as your notions of “cleaning it” evaporate into thin air.

At sea level the air contains 20.9% effective oxygen. At about Black Bear Pass altitudes the effective oxygen drops to 12.7% which is 60% of the oxygen available at sea level. The effect is bad enough to make you wonder what is wrong with your body as you try to will yoursef upward. Another byproduct of low oxygen is generally low mental energy. Picking a line up the scree covered road gets a fair bit more difficult when you are out of breath. One finds oneself gracelessly running into rocks instead of steering around them or finessing over them. I think if I were alone I would have walked more of Black Bear than we did, but the effect of having a riding partner meant that we both dug a little bit deeper to clean sections of the climb than we otherwise would have. I’d look at a pitch and think that it couldn’t be ridden and all of a sudden Peder would ride around me and smash it, forcing me to up my ante. It is difficult to be mediocre when riding with a strong friend.

Black Bear is beautiful. Altitude is gained so quickly and the scenery opens up in such a way that you are spurred on nature itself. In every direction you are surrounded by some of Colorado’s tallest and most beautiful peaks. The dramatic rust colored hues of Red Mountain are visible just to the east. Remaining late summer wildflowers still boom here and there. High mountain lakes and waterfalls accent the landscape. Jeeps drive by as Jeeps do, slowing long enough to ask you if you “rode yer bike all the way up here” and to tell you “good job, you’re cray”.

The summit of Black Bear Pass is less than 3.5 miles from the Hwy 550 turnoff. This surprised me a bit. I had expected a somewhat all day slog to get to the top but despite the steep road and thin air we found ourselves at the pass in just over an hour. I had expected to see a road that eats cars for lunch, but the half dozen jeeps that had passed us coming and going looked no worse for the wear.

Regardless, it felt great to be at the top. The winds were absolutely whipping along on the ridge so we didn’t linger. Obligatory photos are always taken on Rodeo rides though, and the summit was no exception.

After its summit Black Bear descends about ten miles to downtown Ouray. Working with gravity instead of fighting it was such a wonderful change of pace. For the most part we were able to rip down the upper parts of the mountain. On this trip to the San Juans I had outfitted both of the bikes with much larger 47c tires instead of the 38c tires I’d ridden on my previous visit. The difference was remarkable. A rigid drop bar bike can probably never be described as “plush” especially compared to a mountain bike, but bigger tires do make a descernable difference in the rugged conditions that these mountains serve up.

About midway down the descent we started to encounter increasingly rough, technical conditions. It became more and more clear to us where Black Bear’s reputation comes from. The first set of obstacles was a series of tight, twisty technical turns that looked like they would be very difficult with a car’s steering radius. Down a bit lower the road surface turned to a section of increasingly rugged rocky steps. Finally we’d found them. The Steps of Black Bear Pass. I had wondered if they were really that bad, and they genuinely were. We picked our way down them slowly and carefully on the bikes. To our left the creek that followed the road turned into a larger and larger ravine: The one that the Jeeps on Goggle Image Search are seen tumbling into. Our tires on this ride were more of a semi slick file tread and didn’t have great purchase on the smooth stone that made up the road. We more or less skidded our way over and down them until finally it hit one or both of us at the same time that maybe we should dial back the send to 10% and act like dads and husbands instead of care-free kids. We dismounted and walked a bit. It felt good.

It also allowed us to look around. LOOK WHERE WE WERE! The west side of Black Bear is nuts! The creek in the ravine next to us plunged over the edge of a cliff and turned into a water fall and the road appeared to do the same. Far below sat Telluride perfectly nested in a picture book valley. I’ve seen these sorts of views in Europe. Austria and Switzerland have their fair share, but in the United States we don’t often do alpine with the same level of drama. The San Juans are a bit of an exception to that and they add to it with an American cowboy Old West twist.

We stood there for a few minutes soaking it all up. This is the loot we’d come here for. This was The Feeling. I felt very content.

And then the thunder started.

We looked up. While we were focused on the road a storm cloud had focused itself above us. I felt drips of water on my face. Was this rain or was it mist from the waterfall? There was no time to waste It was time to descend. We set the bikes loose down the switchbacks to Telluride. On our way down we passed the famed hydro power generating station perched on the cliff. Yet another mind boggling waterfall emerged just beneath the station turning to mist as it fell towards the valley with us.

We feasted in Telluride. Peder had a distinct memory of a local sandwichery that served fresh calories in baked and sliced form. It was conveniently named Baked In Telluride. We followed the aches in our bellies until we stumbled upon it. It is a bit of an out of body experience to drop in to a town like Telluride in the middle of such a wild ride. One moment you are riding bikes through the jaws of nature, the next you’re munching snacks from a place that is probably Zagat rated. I’d give it two stars.

It is difficult for me to describe Telluride because Telluride doesn’t feel real to me. It is the most just-so place I’ve ever been in my life. Every building, every square inch of real-estate is perfectly tended. It feels like the parts of it that weren’t built yestereday were definitely remodeled yesterday. The town has great skiing, great biking, great hiking, great music, great film, great shopping, great eating, great architecture, and great everything-else. I want to say mean things about Telluride because perfect places can’t possibly be perfect, but really I’d just be masking the fact that I’m jealous that I can’t afford to live there. Telluride is great, but in a nitro-gentrified sort of way.

Telluride is hypothermia to adventure cyclists though. Peder and I couldn’t let ourselves stop and get comfortable for too long lest we forget the danger presented by the afternoon weather. We glanced upwards. The storm to the west that had threatened us up high had seemingly disappeared but in its place a new bunch of clouds had appeared further down the valley towards the east. The mountains rose too quickly for us to have any sort of view of what the larger weather outlook seemed like, but it was 3 pm and the odds were not in our favor that the weather would improve before the day was over.

We were well fed, we were recharged. We had a sense of urgency. It was time then to go about climbing Imogene.

The entrance to Imogene pass from Telluride is completely unheralded. At first the road passes through neighborhoods that hug the lower slopes of the hills. You are greeted with mild conditions. When you do finally see a sign or two announcing a high mountain dirt highway the signs themselves say that the highway is closed. I wonder to Peder if an angry local posted the signs to keep the endless summer 4×4 traffic at bay. I can’t imagine living next to that road as every manner of internal combustion engine parades by from June through September, searching for high mountain Mecca.

My and Peder’s internal combustion engines we a bit worse for wear as we warmed up on the climb, Peder’s less so than mine though. We climbed quietly for long periods. He began distancing himself from me as he rode and as I admitted to myself that I couldn’t match his pace. The more we climb the less I cared about friendly competition. Fatigue set in.

If Black Bear is unexpectedly short Imogene is unexpectedly long and grueling. The climb is wonderful though, at least down low. If you like the proverbial grinding of the gravel then Imogene from Telluride will give you gravel to grind all day long. As you work your way higher it will strew small boulders all over the road along with heaps of lovely views of the valley below. You will once again find yourself out of gears before you are even 1/3 of the way up, a familiar sensation from earlier in the day.

Peder and I found opportunity to talk on some of the milder stretches of the climb. Talking passes time in the most elegant way. Once you find yourself lost in a good topic the shouts coming from your tired lungs and muscles are muffled, if not completely silenced. Peder and I don’t waste time down low when talking on a long ride, we go straight to 50,000 feet. What are we excited about? What are we frustrated by? What are we afraid of?

Good conversations need suitable conditions in which to develop. I would posit that high alpine conditions in increasingly troubled weather, filtered through the lens of fatigue are some of the finest conversational conditions anywhere. Peder and I rode and talked, rode and talked. He related to me the existential struggles of someone who is among other things finely split between children, a wife, and the demands of medicine. I related to him the struggles of someone who is among other things finely split between children, a wife, and the demands of a cycling startup. Bikes and medicine though, those couldn’t be more dissimilar! Except that they aren’t. As we rode and talked our conversation revealed that life is built out of very similar pieces no matter how different things look on the surface. We all want to get it right, we all wonder if we are, we all wonder how we should be doing it better. We’re all fearful of changing how we do things and getting it wrong, or of making things harder on ourselves in the process.

Fear is such a false motivator. Fear will keep you in your bed or on your couch. Fear is the seed of regret. Since Rodeo started in 2014 I’ve more or less lived in a constant state of fear. Life before 2014 was pretty comfortable. I worked hard but I manipulated my schedule deftly so that I can do the things that I wanted to do more or less when I wanted to do them. Income was stable. Risk was low. On the surface all of that was great but I was bored. I wasn’t challenging myself, I wasn’t growing, and I certainly wasn’t chasing a dream. I can barely remember what it felt like to be pre-2014 me. Post 2014 me is much more stressed out, works much harder, has a very demanding schedule, makes a fraction of my previous income, and has no idea what tomorrow will bring. I’ve also never been more excited to be doing what I’m doing. If I can shut the fear up long enough to enjoy the view I’m overwhelmingly satisfied with the endeavor and deeply grateful that Rodeo accidentally ruined my comfortable life. That isn’t to say that I don’t look back. Whenever things get hard I look back to pre-2014 longingly and wish I could teleport and feel comfortable again.

“It’s going to hit us.” Peder said. “But I really don’t want to high tail it back down to Telluride.”

I didn’t want to turn around and go back to Telluride either. Built out of very similar pieces indeed.

Nobody wants to go back down to Telluride. In athletics and in life we all want to keep moving, to keep pushing. Yes, the storms are going to hit us sometimes but hey, hopefully we make it.

The final pitches of Imogene pass were just as much hike a bike as they were riding. On any normal ride it is abhorrent to surrender to a hill and dismount but on the loop that we chose to ride it was more or less inevitable that we would walk from time to time. Of the total forty three mile bike ride I’d guess that we walked about two miles of it. Or maybe we went on a two mile hike with a forty one mile bike ride thrown in? That sounds more virtuous.

We rounded the final hairpin and finally had a straight line of sight up the hill towards the summit. Rain and sleet fell constantly now. We were taking on water. We mounted the bikes, gunned it, then succumbed to the hill twenty or thirty feet later. Pause, breathe, remount. Twenty more feet. Altitude is a nasty adversary.

And then we were there. We were at the top, at the post that seemed impossibly far away not long ago. The wind swirled around us angrily, rain and sleet hit us from all sides. We didn’t have much time to enjoy the accomplishment but I did stupidly, stubbornly force Peder to go take a photo by the sign. I wiped water from the camera lens only to have another ten drops hit it again instantly.

A wall of wind hit and I knew our time was up. There was no warm car to jump into and celebrate. We still had over five thousand feet of wet, cold descending ahead of us. We pulled on all remaining clothing, zipped every zipper as far as it would go, and we bolted.

Much has been argued about drop bar bikes with disc brakes, and how they are unnecessary marketing ploys designed to force us all to buy new bikes, but after our descent of Imogene Pass back down to Ouray I can safely say I owe my life to disc brakes. We didn’t so much ride down Imogene as we did skid, slide, bounce, and swerve our way down. Our teeth were chattering, our hands were numb, and our bodies were convulsing from the cold wind and rain. We were no longer generating any body heat like we were when climbing. Our strength was drained away, conversation ceased, and we rode survivor-style.

These are the parts of the ride were you wonder to yourself if you pushed to hard and if you made a massive mistake not turning around. You don’t feel safe, you don’t feel like you “got this”. Physically everything is miserable and you just want to be done but you can’t be done, you have a huge mountain that you have to slide your way down. An endo or any sort of crash could be pretty catastrophic in these conditions, stopping for a broken bike or broken bones would probably mean hypothermia. Peder and I tried to find that balance of speed and caution, as if there was any speed that could be considered responsible on that day on those bikes in those conditions.

Eventually we hit Camp Bird, emerging from the savage Imogene basin onto more properly tended gravel roads. The temperatures were warmer down low. The wind and rain relented. All that remained was a wonderfully easy descent back down to Ouray. The tension slowly melted from my body. I stopped shivering. We did have this. We’d made it.

As I think back on this ride I consider if Peder and I had been irresponsible in our push to ride this loop. While it is true that we made some mistakes along the way and we could have prepared better for the possible weather, I don’t think that we were reckless. I think each individual has a different threshold for recklessness and we stayed just south of ours. Retrospect is always crystal clear but who is able to accurately gauge the risk and reward of a challenging endeavor before the first step or pedal stroke are taken? We can’t, and that is exactly part of the appeal.

The other parts of the appeal are the elusive feeling of having accomplished the goal, the beauty that we saw along the way, and in this case the shared experience of having done it with a friend.

10 Comments

So rad. Awesome bikes, amazing ride.

Thanks for taking the time to read it!

This is literally the only information on the Internet about cycling Black Bear. I really appreciate it. I’m thinking of camping at Animas Forks and then doing California Pass, Corkscrew Pass and Black Bear with camping at the bottom of the switchbacks or beyond Telluride. No Imogine. Is it safe to assume that 700c with 34 front/36 rear isn’t going to be a low enough gear? I’m in good shape, 8000 miles in 2018 with >350k feet climbing but all at less than 4000 ft elevation. Thoughts on gearing?

Cram as much gearing as it’s humanly possible to attach to your bike. A 34×42 is BARELY enough for the riding up there. The 34×36 MIGHT be enough at lower elevations, but it can’t be stressed enough how steep (and rough) these climbs are. Savage comes to mind. But also, fantastic.

If you gave me the option between a gravel bike with a 34×36 easy gear with 700c wheels – and a mountain bike – I’d go with the mountain bike. Personally. I love my Donkey. Love love love, but the San Juans are a very special realm.

I think Stephen would agree: the San Juans are best enjoyed with big 650b tires (2.0 or bigger), really easy gears (34×42 minimum), and a positive mental attitude toward a little bit of walking. :-)

Sorry, working on an article on this very topic right now for Peloton Magazine. I have a lot to say.

Hope the trip goes well – it’s truly amazing there. You’ll love it. :-)

Thanks. I am going to order Absolute Black 46 & 30 chainrings to go with the 11/36 cassette. A 30/36 combo will be right around the 22 GI range of the 34/42 setup described in the article, assuming 700c wheels. Were the bikes in this article using 700c or 650b wheels?

As an aside, I’m lusting over a TD 3.0 which would replace my Niner RLT 9 RDO frame for some of the reasons being discussed. Or maybe just a fresh build :)

Again, I really appreciate the response.

-Tim-

We used 650b x 47 on this ride. We’ve done riding up here on 40mm tires and technically it is possible but going from 40 to 47mm made a WORLD of difference and going from 47mm to 54mm (2.1″) also made a huge difference. More isn’t always more but on these rides more is definitely more. That 34×42 is another example of this. Technically it’s sort of passable and we did it but 34×46 is strongly recommended. This type of riding is exactly why we evolved from TD 2.1 into 3.0. We wanted to do more riding in the San Juans and similar and we needed the bike to be just a bit more capable in order to make the rides more enjoyable.

Agree with Jered. You won’t enjoy it on a 34/36. You should have a MTB drivetrain on your bike on these climbs. 34 front minimum and a 42 minimum in back but really you should just go with a 46 in back.

700c – same. With anything smaller than a 40mm tire it is very questionable. On this particular ride we were on 47mm which was actually decent for us. The bigger the better though. If your bike can go bigger go bigger because the last thing you want to do is struggle up the climbs and then suffer on the descents. The descents are just better on bigger tires. I would tell any normal person to just do it on a MTB but I’m plenty happy doing it on our bikes.

We’ve also done California and Corkscrew and they are no less steep and gnarly than Imogene or Black Bear. Doing all three passes in a single day is do-able if you are very fit. Be prepared to get nuked by the weather. Cold weather gear and a space blanket to hunker down if you need to let a squall blow by.

Thank you. I’m building lots of flexibility into the plans in case of weather and planning on options like heading into Ouray instead of doing black bear, things like that. Really appreciate the response(s).

Great write up. Thank you!

And major kudos on the ride.

Do you have a strava link to this? I just looked at segments on the map and there is a whole mess of crazy routes around there!

I was wondering how the steep rock sections compare to the horrible cinder rock section on Mauna Kea – which I got through but then gave up 900ft from summit because of lack of time, energy and a will to live….

Wondering if I should try Black Bear on my ElliptiGO.

Eliptigo is 1000% the way to go if you want nobody to find your body. The route we took is easy to follow. It is very difficult, but it’s doable and we didn’t have to climb over any bounder fields:

https://www.strava.com/activities/1171960216