It is only 14 hours later if we pick up the telling of my Atlas Mountain Race story from the Journal entry that I posted the night before it started. It is finally the morning of race day itself.

In the real world however it is exactly five months later as I write this. Five months have passed since the race start at 9:00am, February 15th, 2020. Collectively it feels like lifetimes have passed since that day. In a way it feels the world that existed in February doesn’t feel like it exists anymore. So much had changed. The world moved on.

And yet even if the world has moved on I haven’t. Like everyone else I’ve been swept along mercilessly by what life has become in 2020: The Pandemic, quarantine, economic disaster, then a cultural shift, awakening, riots, protests, calls for reform, and now a new wave of pandemic, and after that an election beyond which nobody could possibly guess. It feels like February 2020 never happened. It feels like I never went to Morocco. And yet I know that I did because in my mind I’m different for having gone and I will never be the same. Physically the signs are still there as well. My bike has the scratches and scuffs. My helmet straps wore bald spots in my beard and scalp that won’t grow back. The fingers that I’m typing this with still can’t fully feel the keys that they are typing on, their nerves are permanently altered by the abuse inflicted upon them by the Moroccan landscape. But mostly I know I went to Morocco because the story is so fresh in my mind. In the rare moment that life quiets enough for me to pause I can journey in my head right back to those endless dirt tracks passing through similarly endless mountains made of the earth’s very crust and rocks piled high on top of it. I can still hear the sound of my tires as they ground infinite pebbles beneath them. In my mind I can still see the sunsets with palettes so subtle that no camera could capture them. I can taste my perspiration as it rolled past my singed, chapped lips and into my mouth where it stung my swollen tongue. I can feel the fear of being totally unfathomably alone in the pitch black of the moonless night, near the tip of the African continent.

2020 may have moved on but Morocco is still there. The school children who waved at me in the village that Google has no name for are still there. The shopkeeper who on the final morning sold me that warm fresh bread that brought me back to life is still there. The women walking down that canyon riverbed at dawn, resplendent in iridescent colors, scoffing at the monotone landscape are still there. The shepherd tending his three sheep in the driest most desolate plain I have ever passed through is still there. Part of me is still there as well. Tiny minerals, star dust, forgotten drops of sweat, and microscopic fragments of my DNA are still somehow now there, dispersed across seven hundred and thirty five miles of beauty and barrenness. It’s all still there.

So if Morocco is still there then why not go back? Why not revisit the memories good and bad and reflect on them one more time? Why not try to finally distill what I think I learned there? Why not put 2020’s overwhelming realities on hold for just a bit, and return to where we last left off: The starting line of the 2020 Atlas Mountain Race in Marrakesh, Morrocco.

Boundless optimism. That is the only way that I can describe the collective feeling in the crowd of racers that gathered in the cool of the morning at the Mogador Kasbah hotel in Marakkesh’s official Zone Touristique De L’Agdal. The hotel itself was executed exactly to the minimum possible standard while still maintaining a feeling of latent luxury combined with cultural cliche. At every angle our curated surroundings seemed desperate to remind us that we were in an exotic, romantic, enchanted country. Without the ornate carvings and intricate mosaics however, one could have drawn the exact same conclusion by simply stepping outside, turning 360 degrees, and letting the true overwhelming beauty and activity of Marrakesh itself tell you that you were in fact in an exotic, romantic, and enchanted country – one that overflowed with a wealth of history, tradition, and culture that needed no amplifying to appreciate. Morocco is bonkers. Go there some day and when you do try to avoid curation. If you do brace for impact and prepare to be changed.

A spectrum of world citizens were represented at the starting line of the race. As an American I would have thought rather obviously that American’s are pretty central to bikepacking culture. But the truth is that Americans were the exception at the starting line of AMR. Europeans were far better represented than Americans and to my recollections those hailing from Scandinavian countries seem extra keen on the sport. Britons, Germans, French, Belgians and others mostly completed the happy mix of well geared and overly fit people that I saw as I looked about the parking lot. We lined up with a proper mixture of nerves and confidence. There were plenty of veterans in the mix but also just like me there were a handful of first time racers just now dipping their toes into what amounts to a fairly short bikepacking race when compared to other more absurd races such as Silk Road or Tour Divide, each taking 1-3 weeks to complete.

We Were All So Prepared as it were. We’d checked our spreadsheets, chatted in forums, packed and repacked, calculated gear ratios, packed last minute wares, and unpacked other last minute wares. Bikepack racing sometimes seems far more about the actual act of packing your bike with gear and provisions than it is about the actual act of racing your packed bike from point A to point B. And to that end we were already all World Champions of stuffing things into nylon sacks and fastening both Velco and Zippers. We were a collective podium of about 180 racers ready to Do The Thing. Little did most of us know that The Thing was about to do us.

“Bang, whistle, pop, GO!”. I can’t remember how the race started. I know that people began moving and that already I had made a mistake: I didn’t even have my course map loaded. No matter. We were off and it felt GREAT to finally be moving under our own power towards a finish line so many hundreds of miles away. When preparing for an event like this one begins to feel a bit pent up as the stress of the impending endeavour seems to build like a towering thunderhead. Every day in the run up to the race your emotional and physical investment ratchet higher and higher as the start day on the calendar looms until finally just like this morning on February 15th you finally unleash all of that tension and investment in the form of overly intense pedal strokes pounding one after another. I had thought that with 750 miles to cover we might begin AMR at a fairly civilized pace, but right from the start the pace at the front of the group shot up to something far past what I would deem reasonable or measured. I looked around for a sympathetic rider with which to discuss my objections but none could be seen. Everyone else was smiling and happy to motor right along. Instead of showing evidence of my distress I decided to fake that I was OK too. If were were all going to detonate ourselves before we left the city limits of Marrakesh then so be it!

We formed giant pacelines.

We tucked.

We fled the city towards the mountains and towards our glorious fate. We were bikepack racing after all. “Beers in Agadir!” was the war cry of the bold and the naive both.

The first tens of miles of Atlas Mountain Race were a euphoric dream. It is difficult for me to find words to express how happy I was to be there in that moment striking off on a grand adventure the likes of which I had never even nearly hoped to participate in. I am terrified of huge things. I am afraid of the unknown. I want nothing less than to be outside at night. Deep down I am a man that loves comfort and familiarity and it is only in fits of insanity and impulsiveness that I am able to break free from the clutches of that man and become someone adventurous. These out of control moments in life, those of flying down an African dirt road with a hundred smiling strangers are the things dreams are made of. Dreams in which I’m someone exceptional and exciting, not routine and predictable. I think back on those miles now and am filled with gratitude. To have lived them, to have experienced them and soaked them up. I am smiling as I write.

The climbing began shortly thereafter.

The miles up until now had been out of a bike touring catalogue. The roads were mostly flat and rolling. The villages were quaint. The flora was verdant. The northern costal side of the Atlas mountains receive much more rainfall than the arid southern sides and we enjoyed every manner of crop and harvest being cultivated in the valleys and on the hillsides.

As we finally completed our traverse towards the foothills our legs were given their first true tests of the week. They were now warmed up from those fast early efforts and by now most riders within my sight had let off the gas and found something approaching a more sustainable rhythm. I struggled to wind down my own legs. I had trained quite hard for these moments, for this race and I knew beyond a shadow of a doubt that my engine was primed and prepared to do the work. I began passing riders and made note of those that I was passing. Already some were experiencing flats or mechanical issues that had caused them to stop. Some riders appeared to struggle in the initial off road dirt tracks that we encountered. Where others braked I didn’t, where others coasted I pedaled. It wasn’t competitiveness that drove me along, instead it was the pure joy of riding a bike and feeling in control of it. Everything was working, both man and machine.

In the middle of that I set about mentally cataloging what I was seeing. Just look at this place! Steep slopes of the Atlas Mountains met in narrow valleys, themselves filled with creeks, rivers, villages, and groves of almond and olive trees. School children mashed their faces into metal gates at recess to cheer us on. Piping hot tagine stews cooked slowly outside shops along the road, filling the air with flavor and spice. Groups of men looked up and stared as we passed. Most women avoided eye contact but many called out “Bonjour!” as I rode by. I will admit to a certain amount of trepidation at the prospect of racing mostly solo through such an unknown country and culture – my Western biases crept in the shadows before the race. But once there in that place face to face with the real people who lived in these towns and villages I was only greeted with hospitality and warm welcome.

I rode onward into the mountains and up the long climbs of the day. Strava told me that approximately 17,000 feet of climbing lay in store for me on the way to CP1 which sat about 75 miles from the start of the race. Other route software such as Ride With GPS says that the elevation was closer to 13,000, but no matter which metric was route none could deny that this was not normal climbing. I never actually weighed my Traildonkey before the race because I thought that doing so would put a number in my head that was so scary that it would haunt me for the entire race. But if I had to guess I would estimate that my bike fluctuated between 40 and 60 points depending on water and food that I had stashed aboard it. Climbing with that much weight is an act of willpower as much as it is an act of fitness. Climbing over a mountain range with that much weight in tow, well, that’s just bikepack racing.

Surprisingly I felt ok climbing all day long. I mean that in the least smug way possible. The first summit of the day topped out at about 5,700 feet before we enjoyed a blazing descent into the town of Zerkten. Near the summit of that climb I began noting a certain fatigue beginning to show in a number of riders that I was passing and it occurred to me that a lot of riders in this race lived at or near sea level whilst I my home city of Denver sits squarely 5,280 feet, just slightly lower than this fairly dramatic pass. While others struggled with thinning air I motored on none the wiser. I was quietly grateful for this hidden superpower. I had done nothing to deserve it yet it was mine to enjoy. At 180lbs I cannot be considered a svelte climber, but in these unique circumstances I felt strangely at home pedaling my laden bike uphill with maybe slightly more blood cells supporting the effort than were enjoyed by most of my road mates.

Zerkten couldn’t be anything but awesome. After topping out on the large climb we were treated to the most serpentine of descents down a lovely paved highway towards the town – and resupply at the bottom. I was in full tilt race mode at this point and pretty stocked with food so I tried to make a quick escape after refilling my water and Coca Cola reserves. Water is an obvious beverage on any bike ride but Coca Cola is the one true sports drink that packs all of the chemicals necessary to propel you through the next thirty chemically enhanced minutes of your life. Salt, sugar, and caffeine are quite the potent mix and quite often you could find one of my bottles filled with a warm, flat 24 ounces of Coca Cola. But beware: Once you get on the Coke train it can be quite a miserable experience to get off of it. If all you have coursing through your veins is napalm you’ll experience quite the catastrophic nutritional crash when the napalm suddenly burns out. So buffer your Coke with other goodies like peanut butter, bananas, hard boiled eggs, pickles, or whatever else you can gather from a road side shop and force down your throat.

Climb number two of the day was The Big One at about 19 miles in length and climbing somewhere between five and eight thousand vertical feet depending on what software you are looking at. This moment in the race was for me the first moment where you just put your brain into 4wd low and powered out endless hours spinning the cranks by any means possible. On the lower parts of this descent I passed probably the best overall bikepacking racer out there, James Hayden. He was moving along at a very relaxed pace, so much so that I thought that he might be unwell. I smugly patted myself on the back for passing a legend and continued on. Other riders came and went. Sometimes I would ride with one or another for a few minutes but ultimately I dropped every single one of them. Nobody passed me on the 19 mile climb. This was a due to a combination of what I would soon learn was a foolishly fast pace and the fact that most of the racers who were faster than me were already ahead of me never to be chased down. Still, it felt great to see a dot up the road and set about reeling in the dot until a person who appeared to be suffering more than me came into view. As I think back now that first day of the race was really the only time in the race where it actually felt a little bit like a race. On day one I wanted to beat other riders. In subsequent days I simply wanted to survive and not humiliate myself.

The paved road turned to dirt. The dirt road turned to a steeper dirt road. The steep dirt road turned to a ridiculously steep series of switchbacks in the way that roads do when they suddenly realize that a 4%-6% gradient will never be sufficient to reach the pass in the distance. At that point the road gets bitchy and goes straight to 10%-20% gradients. I remember seeing those switchbacks in the distance and sort of laughing at them as if they couldn’t possibly be real. About a half hour later I was crawling up them. This road was real, but that fact that we’re still calling it a road is a little silly. I saw about four to six racers on that road and nobody looked happy. Some walked, some tried to ride the whole thing. I was in the latter group and I’m fine admitting that I failed to ride it all. Walking felt WONDERFUL now and again. Me and my Donkey walked and road and rose to meet the pass.

I had been reading about this, called Tizi n’ Telouet ever since the day I applied to enter the race. It loomed in my mind like Tolkien’s Mordor, a dark, black, evil pass full of unknown and danger. I had imagined what it would be like to summit it’s 8,500 foot saddle. I expected a blizzard and one had indeed passed this way within a week of me being there. But as I summited I found the place quite serene and not particularly threatening. In so many ways the pass was not much different than so many similar passes that I have traversed in my home state of Colorado. Even halfway across the world as it was, this place felt like home. Atlas Mountains, meet the Colorado Rockies. You two would totally get along.

It was later in the afternoon by then but I had hours of daylight left. I was incredibly grateful for this. Earlier in the week other racers had scouted this area and had reported the back of the pass to be a nasty hike a bike down the mountain. The road disappeared entirely at the summit and only a poor excuse for a goat track remained to thread its way through miles of scree and boulders. Some who had scouted had reported losing the route and getting lost for hours in the process. Those reports had sent shivers through all of the racers who heard of it. It suddenly became the goal of most people to hit the pass before the sun set so that we would have time to route find down the hike a bike with the help of daylight instead of being lost in the dark at 8,000ft with no trail to follow.

I struck off into the boulders and scree on my own. To my left down the slope I saw two racers descending but I could make no sense of why they were heading that direction. The bread crumb dots on my GPS led me to the right and I followed them religiously. There did seem to be no path at all and it took a lot of faith to follow pixels instead of my intuition which was to follow the other two, but I stuck to the route and eventually ghosts of a trail emerged here and there, and never for very long. Yet this too felt familiar to me. Once again making our way through alpine scree is something we’ve done a fair bit over the last few years in our crazy Rodeo Labs explorations of our native mountains. Nobody loves lugging a heavy bike over boulders and down ledges in lieu of groomed trials and roads but one must do what one must do when endeavoring between point A and point B. After a half hour of this silliness a trail appeared. The trail itself at times threatened to turn into a road but never fully did. The going was rough. I stubbornly tried to ride a lot of it. An endo took the edge off my ego. Why risk everything to clean a line when walking was nearly as fast and crashing could cause gear to be damaged or a bone to be broken? Pride quite literally goes before the fall.

About halfway down the descent I was finally able to to remount and ride. I passed a Scottish fellow walking alongside his bike on which were mounted fairly skinny tires. He looked miserable. “How are you riding this!?” he asked. “Lots of practice!” I responded. Six years of stupid rides over questionale terrain on a drop bar bike were paying off in spades. Long live drop bars on dirt!

As soon as that happened though I was right back off walking through another section of boulders. My fingers slipped and hit my shifters without me knowing forcing my derailleur into the granny gear. With no movement on the pedals the chain did not move and the derailleur snagged the granny gear. I felt resistance in the rear wheel but I kept walking. The resistance built until alarm bells filled my head. Something was very wrong. My rear wheel wouldn’t roll and the derailleur started making a very sick sound. I looked down just in time to see the beginning of the end: The derailleur was being ripped off the bike.

NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO! I screamed out loud. NO NO NO! This couldn’t be happening. NO. I couldn’t have my derailleur destroyed on day one of the race! I stopped. I gingerly went to work untangling the mess. Eventually the wheel could spin and the derailleur remained attached but I could tell that the system was damaged. Strange noises were coming from the whole assembly and once back on the bike pedaling I could tell that my shifting was no longer correctly calibrated. I had either bent the derailleur, the cage, the hanger, or all three. That said I was still alive, the bike was still mostly serviceable, and utter disaster had been ever so slightly averted.

“Slow down Stephen!” I yelled to myself. It became clear to me that I was riding and racing like an idiot. From rushing through the resupply stop to climbing to quickly to trying to clean the switchback climb to trying to ride the goat trail descent I was making impulsive short sighted decisions that one by one were adding up to a non sustainable race strategy. “You need to slow down and re engage your rational brain instead of your excited bike racer brain”. That was the point that something changed inside me for the duration of the race. No longer would I be as impulsive. No longer would I ride closer to the edges of my ability or fitness. In the late afternoon of day one of Atlas Mountain Race I stopped behaving like a bike racer and started behaving like a bikepacking racer.

The remaining miles of descending down the mountain were flowy and fun. I continued to lose and regain the trail from time to time but my pace was good and I did not suffer the fate of the course scouts who had gotten lost. I entered a small town called Telouet and bought fresh water from a street vendor before continuing on. I still was not fully mentally present after the near miss on the descent and had no idea in my head that I had indeed arrived at CP1 until I rounded a bend in the road and saw the CP1 sign hanging in front of Chez Ahmed. Utterly dumbstruck I dismounted my bike. CP1 already? How could that be?! This was incredible news! I was covering some serious ground!

I had my race passport stamped and signed the rider log. To my total astonishment I noted that I was currently in 10th place in the race. TENTH PLACE. I had no idea how that could be. I mentally rewound through the riders that I had passed all day. Had there been that many? Were there really so many people still behind me? Were there really so many riders even now still climbing towards the summit of that pass or descending down the hike a bike? It didn’t make sense but I was happy for the news.

“Would you like some dinner” someone asked? I had just stopped at the shop a mile prior so my water and coke were already topped off. I made a quick decision to keep going and remounted my bike. Then for a split second more I thought about my food situation? How much food did I have with me? I wasn’t even sure? SLOW DOWN STEPHEN! Slow down. I stopped and turned back. I needed a real meal. I laid my bike down and walked up the stairs into the courtyard where a table waited and a chicken tagine stew was ordered. Real food would be good. I had an hour or two of daylight left. I needed to steel myself for the coming night.

While I waited for my dinner James Hayden arrived at CP1 then appeared at my table. As it turned out he wasn’t sick at all he had simply been pacing himself like a veteran racer. He made good work of the climb and absolutely shredded the rocky descent on his mountain bike which unlike my gravel bike had the benefit of front shocks. He was in great spirits and sat down next to me. He asked about the chicken tagine but instead ordered soup because it would be quicker. Hearing that I also ordered the soup and canceled my tagine. If a legend sits down next to you at dinner to good move is to do whatever they do and take the time to learn good bikepack racing technique. Dwelling at checkpoints and resupply points does nothing to move you closer to the finish line.

On that thought I was soon off again. The scree fields and hike a bike had now become an absolutely lovely smooth paved descent at golden hour. The road was serpentine and surrioundings beautiful. This was one of those sublime moments of the race that once again I will always remember fondly. Warm air, velocity, high spirits, and a full belly. All were mine as I raced down that road. I truly had no idea where I was going or what lie in store next and for a brief, stand out moment in my life none of that mattered. There was only now and now was good. These singular moments of clarity and peace are some of my favorite takeaways of the Atlas Mountain Race experience.

The descent finally ended upon sighting a group of Moroccan policemen parked in the road signaling at me. Had my American nerves proven reliable? Was there danger around every corner? Were they there to detain me? Of course not! They waved wildly as I blasted by and then realized my error. I flipped the bike and they signaled me across a bridge and back onto the course. They were simply making sure racers were looked after properly. Typical Moroccan hospitality.

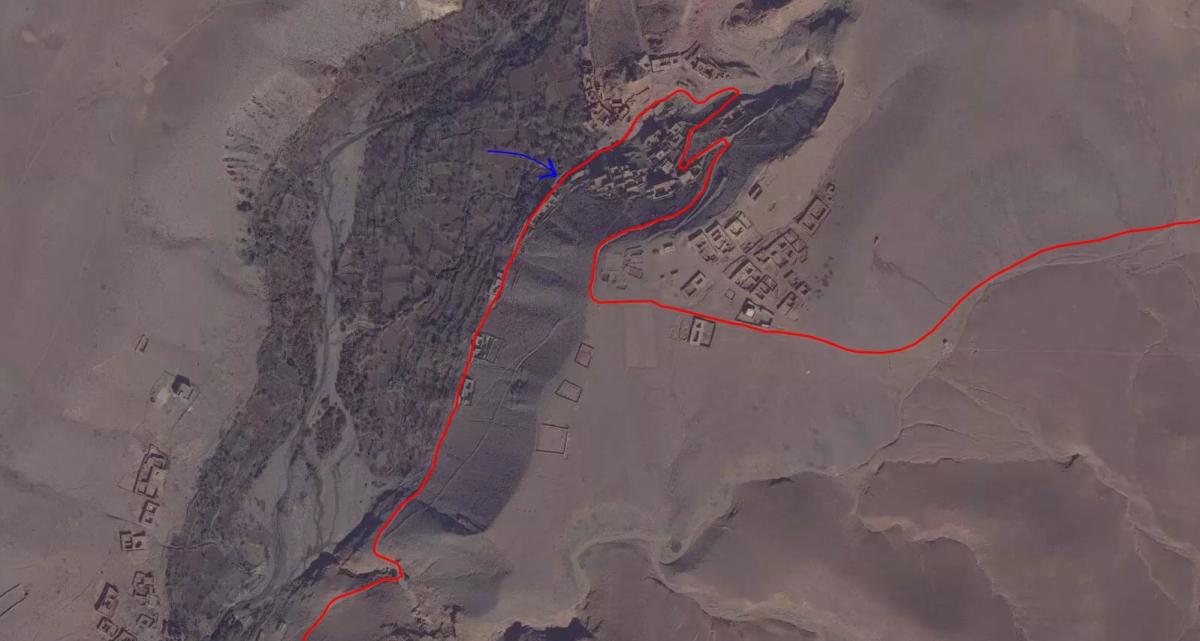

I entered the outskirts of Anmiter and different type of terrain and history at the bottom of the descent. Dusk was beginning but enough light remained to illuminuate my fantastic surroundings. I navigated a tight, technical donkey singletrack through mud brick buildings resembling castles and casbahs. The structures towered over me and look down at me silently observing my passage. No doubt countless donkeys had walked these paths ferrying wares, spices, and people over the centuries. Now here I was on my own mechanized beast behaving similarly but differently. I had no trade to ply with the locals. I was merely feasting with my eyes and passing through in haste, but not with so much haste so as not to appreciate this place and all of its magic. Along the trail almond trees blossomed on either side. The sound of laughing children ricoched between homes made of dirt and cenment. The path wasn’t always obvious. I followed my GPS bread crumbs through the maze, it’s tightness often triggering an off course warning followed immediately by the happy chime of a course found. It was not yet sunset on day one and I had found adventure, I had found history, I had found mystery – all by bicycle, powered along by only my legs and lungs.

A very steep 500 verical foot climb took me up and out of that valley. I looked back already melancholy. It was sunset. Anmiter and it’s brief magic was beginning to twinkle behind me. Modern buildings mixed in with the ancient decaying castle-like towers, their electric bulbs betraying the fact that I had not gone back in time I had merely passed through some people’s modern everyday life. This was the constant reality of Morocco that hit me in waves, over and over: Modern life and ancient history co-mingle there. There does not appear to be animosity between the two. Both are equally present, equally real, and equally appreciated in a way that I wish my culture would emulate.

Hours had passed since CP1. I was now on the top of what seemed like a rolling but mostly flat plateau that extended indefinitely into the distance. From my vantage point I could look back to the north west and see that I was now leaving the mighty Atlas Mountains behind me. As difficult as they were to climb I was sorry to see them go. I love the sense of being in the mountains. The rising and falling of the peaks contain the endless possibility of things to be seen and discovered. Now as I drew away from them and encountered this rugged plateau the openness scared me because I could plainly see how impossibly far I needed to ride. Any visible horizon was potentially one that I would need to ride out to meet today, and then again tomorrow tomorrow, the next day, and beyond.

I stopped and ate some canned tuna.

My on the bike sugar snacking wasn’t agreeing with me. It was time for some straight up protien. I haven’t eaten canned tuna in decades. It was very dry, very wonderful, and very difficult to get down. I stared at the sunset while I chewed and coughed, hoping some saliva would kick in and get to work. I vowed to wait until the sun touched the mountains before continuing. This was a gross waste of time for someone in the top 10 of a race, ostensibly trying to move as quickly as possible. But who cares? When would I ever see the sun kissing the Atlas Mountains again? Will I ever? Typing question out is a little bit scary and depressing.

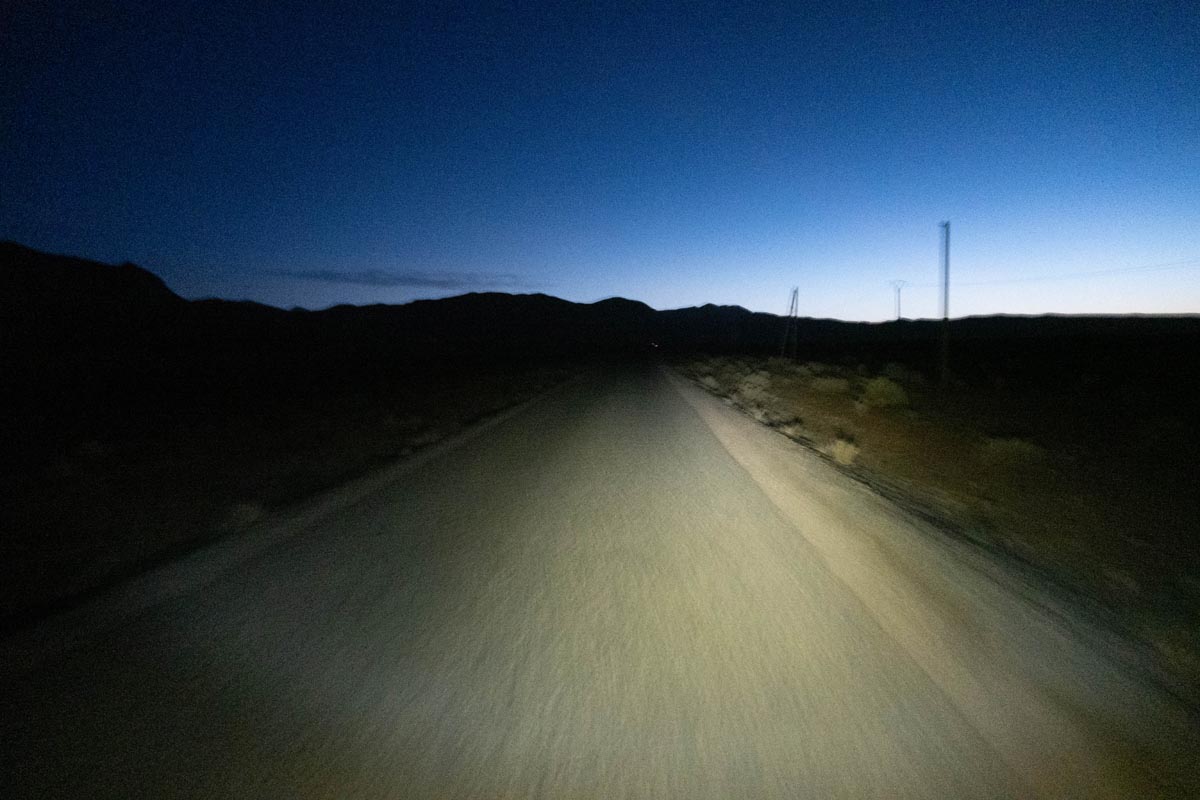

Darkness came. I switched my dynamo powered headlight from accessory charging priority to “light my way” priority. It sputtered and gave me very sub par illumination. Oh yes, I thought, I’m barely moving along and a dynamo generator hub doesn’t work very well unless your wheels are actually spinning.The very rough terrain and fatigue impeded my progress and my headlight output. Fine then. I unplugged my USB power bank from the charging port of the headlight and directed all available electrons towards the singular task of illuminating the primitive road beneath me. Visibility improved.

A headlight appeared behind me in the distance. I wasn’t sure if I was happy or sad to see it. I had been expecting to be overtaken since leaving CP1, and while company out on the road could be a nice way to pass time I also resented the idea of anyone traveling faster than I was. From what depths did this reaction emerge? Was it the ghost of my road racing days recalling the competitive urges of a decade younger version of myself? No. That wasn’t it. It was my insecurities kicking in, insecurities that I didn’t belong out here and that I was a fraud. In the days leading up to the start of the race in Marrakesh I watched other racers congregate at the hotel. Handsake-hugs of friends reuniting were exchanged. At dinner war stories were traded of “that one time at the Trans Continental Race” or the Tour Divide or the Silk Road. Everyone around me seemed like they had the swagger of a veteran bikepacker, and then there was me. Before Morocco I had never bikepacked. I had never ridden to a place with all my gear on my bike and spent a single night out under the stars. I felt like a fraud, like I really didn’t belong at the race and yet here I was with a rediculously nice, brand new bike with matching bags filled with an ultralight tent that had never been pitched much less slept in. The light approaching me from behind was a reminder that there were faster, more experienced, and more talented people out here and that they were chasing me down. Despite having a great ride to CP1 I had a dreadful sensation that my race would inevitably come crashing down and that my lack of experience in this discipline would be exposed. I wanted to be here. I wanted to put up a respectable ride at this race, but I was very scared that ultimately I would crack and that I would fail.

I upped my pace. I didn’t want that light to get any closer, and it didn’t, for a while.

Miles pass strangely in the darkness. There are no visual markers on which you can affix memories. There is only a tight, flickering beam from your headlamp and that makes for an extremely poor memory trigger. So I drifted for an indeterminate amount of time. The road would rise and fall, rise and fall. Sometimes it was smooth gravel but mostly it was comprised of large, sharp rocks that threw dazzle camoflauge shadows. I remember nothing of that time until I began a sharp descent.

Even though I was riding a rigid gravel bike I had set it up well for this weeklong task. My bars were bolted to a suspension stem that allowed 20mm of vertical compliance and bump absorption. My 55mm tires had penty of volume and low enough pressure to aid even more with the suspension effort. Under my butt was also an eleastoer suspension seatpost providing another 20mm of spring which intercepted countless millions of vibrations before they had a chance to run up my spine and cause my 41 year old discs to bulge and beg for mercy. Insomuch as you can call a gravel bike plush my bike was plush.

My bike was plush and I rode it with confidence. I plunged down the steep descent into the darkness and my headlight brightened as if to spur me on. A late night shred down a forgotten Moroccan dirt track? Why yes I don’t mind if I do!

CRACK! The descent ended abruptly and without warning in a dry river bed. Being a river bed the small rocks had long since been swept away by water and only larger rocks remained. Larger, more damaging rocks. The crack was skull shaking and violently loud. If you’ve ridden a bike long enough you know that sound. That was the sound of something breaking. Another sound also erupted: One of escaping air. My brain connected the dots. I had struck a blind rock in the dry river bed, bottomed out my tire against my now possibly broken rim and had snake bit or cut my tire in the process. My dymano powered headlight was now doing nothing as my wheels were not turning. I turned on my battery powered headlamp and had a look. A guyser of tire sealant was illuminated by the blue LED beam. Tire sealant is liquid gold that fills a tubeless tire and typically seals leaks instantly in the same way that blood clots in a wound. But if the cut is big enough the tire bleads itself to death as you watch on in horror. I ripped my glove off and plugged the hole with my fingertip. The leak stopped. I removed my finger. The leak sputtered. Plug, sputter. Plug, sputter. Would it seal with some luck? Too soon to tell. The tire was nearly flat so I decided to hit it with some C02 for a quick refill. Air pressure re-ignited the guyser of sealant.

Fuck.

I don’t swear around my kids. I don’t swear around my wife. I do swear on my bike.

I swear at motorists who almost hit me. I swear at myself when I almost crash. I swear when my tire won’t seal in the dark, moonless night of North Africa. Sometimes a word is required that instantly releases the emotion that you feel in that moment. “Crap” won’t do. “Darn” won’t do. “Dammit” won’t do. Only a solid F-bomb captures the moment.

Fuck Fuck Fuck.

Sometimes it takes three of them . This was a three Fuck situation.

The tire lost air but stopped short of of going entirely flat. I decided to walk for a moment to collect my wits. At that moment the headlight that had appeared behind me shone brightly just at the top of the descent that had mortally wounded my tire. My mood darkened. Who was nameless rider catching me during my three fuck situation? Their timing couldn’t have been worse for my mood.

“Hey man” said James Hayden in his British accent as he slowly rode by. He instantly surmised my circumstances like any veteran would but didn’t really pause for long. This was a race. Let the dead bury the dead. Dogs barked around us in the night. We were on the outskirts of a very small village. “Watch out for the dogs” he said as he continued on. The glow of his headlight soon vanished as I plunged back into the very heavy darkness of the night.

I continued walking. Dogs circled around me. I yelled and threw some rocks. They seemed to keep their distance, or were they just biding their time? The hair on my arms stood on end. Could they smell my fear? If they could I was a goner. I tried to sound powerful and kept moving.

When I could take it no more I tried adding a little bit more air to the tire. Amazingly a third sealant eruption did not occur. I could hear no escaping air. Had it sealed itself then? Should I try to ride it? I threw my leg back over and pedaled slowly and carefully. Maybe it would hold long enough to get me away from the village with its sleeping inhabitants and angry dogs.

A half hour passed and all was well. I added more air and picked up my pace. Occasionally in the distance a red light would flash. Was that a tail light or a cell phone tower? Even in remote parts of Morocco cell phone towers were not entirely unthinkable as it is much easier to build a wireless phone network than it is a wired phone network. The red flashes of 4G LTE antennaes were often my only companions at night during the entire race.

In this case the red flashing was in fact a tail light and I slowly caught up to it. Once again it was James. I asked him how he was feeling. Good but not 100%. I confessed that when I had first passed him earlier in the day I thought something must be wrong with him.

“No” he said. “I always start slow. I find my own pace. Everybody races by but they will eventually slow down, I will find my rhythm, and I will catch them. Maybe all of them”.

Wow. That was confidence talking. That was experience talking. James projected everything about himself that I didn’t feel about myself. I wondered what it felt like to have this situation, this race, seemingly totally under control. I felt a pang of envy. I wished I had what he had.

A strange thing happened. I pulled away from James again and he disappeared behind me. It wasn’t intentional but I too had a pace that my legs wanted to go. Was it an experienced pace? No. But in that moment it was my pace and I felt good having at it.

I didn’t much like the miles that came after. I felt very alone. The euphoria of Day One had all but dwindled. The darkness ate at my morale. Moroccan darkness in February is the darkest darkness I’ve ever ridden in. The sun set suddenly and with very little warning. When it did it left no moon as consolation. Even the stars felt dim to me. You don’t know what true darkness is until you’ve been in a cave deep underground and turned off your flashlight. The tutal absence of light feels inhuman. That is absolute darkness. For some reason Moroccan darkness felt absolute as well. Absolutely dark and absolutely alone. Absolutely tired and absolutely hungry. My water dwindled.

I climbed an extended hill that felt like a mountain pass but almost certainly wasn’t one. I had no plan. I kept riding. Riding is what I had come here to do. The sensation of being absolutely alone persisted. When I felt most alone something sudden and very good happened: The dirt track that I was on became a paved road, and a gently descending one at that. Eureka! Paved descent to the rescue. Far far in the distance I could see the horizon lit by the glow of a larger city. Ouarzazate. I seemed to be riding towards it. I imagined a restaurant or hotel. A place to lay my head. The road rounded a bend to the left and the glow pivoted to my right. Our paths were never to intersect. Back into the darkness I rode.

Mile 113.2.

Eventually I came upon a small village with cement buildings. One was lit from within. I stopped and stared to make sense of what it was. Was it a store? Should I buy some water? Inside were a group of young men around a table about 20 feet away. They looked up and saw me. One came outside and asked me a question in French or Arabic. I was too tired to descipher which it was – a fact that I’m embarrassed to admit. I responded in pathetic English. “I’m sorry I only speak English”. The man dissappeared back inside. Another young man came out with him.

“Hello! Do you speak English?” came the fluid words.

“Yes!” I responded.

“What are you doing here? Where are you from?”

“I’m from Colorado!” I replied, trying to be vague about the USA part lest that somehow put me in bad light.

“Welcome!” He said. “Thank you for coming to my village!”.

Um. Thank you village for even existing!

“Do you need anything” he asked?

“I’m very low on water.”

“Yes! One moment.” He entered the building and brought out a large pitcher. He refilled my bottles. I thanked him profusely. Wow. Water! A human! Light! Men gathered around a table talking! It all felt like a dream. Too good to be true.

I’m thinking back now on that moment as I write this. It is difficult to believe it ever happened. It is difficult to believe that village is still there and that those men may gather around that same table tonight. How did I hit the lottery in space and time that I can cross the world, hop on my bike, meet a group of men, watch them serve me water, then dissappear again back to my life, my world, a half a planet away? Our lives intersected for the most brief, most critical moment for me, and most likely they will never intersect again. I’m sure I told them thank you. To have not would have been a lifetime of regret.

If I had to wager a guess it was now 10pm. I had been riding for 13 hours and things get hazy at this point. The paved road hung a left after a series of sparkling new buildings that I imagined was some sort of university or Islamic school. As it did it became dirt again but not a small dirt track. This was a wide graded undulating dirt road the likes of which indicate that the modern world is close by or that you are on your way to a place that matters. For me the road mostly meant that my way through the night was smoother and less fraught with navigational challenges. My mind was on cruise control, but my belly and my body were in steep decline. Nearing midnight my engine had more or less had enough of the particular type of gasoline that I was feeding it and I began my first revoltion into the nasty spiral that is “I don’t feel well so I won’t eat, but because I am not eating I keep feeling worse and worse”. That kind of feeling is a hollow feeling. Your veins feel full of air, not blood, and your legs resist every instruction to continue their infinite circles.

At mile 125 I reached the end of the map. I’m not sure that I’ve ever done this and I wasn’t expecting it. My map consisted of 1/6 of the race course only and apparently I had completed about 1/6 of the race because as I looked at the bread crumbs that I was following on my Wahoo screen they simply stopped. It is funny to think about how simple these circumstances are, but deep into the night in a tired and mal-nourished place I felt a stab of fear. I had lost my trail of bread crumbs and was no longer certain where on planet earth I was or which direction that I needed to proceed in to get found again. Suddenly it hit me:

“Stephen maybe you should just calm down and load the 2/6 segment of the race course.”

I did that. The bread crumbs came back. I was un-lost, apparently still in Morocco, still racing my bike through the night.

My downard spiral continued with every minute and every hour and water was soon added to the list of concerns. I was down to less than a bottle with no real idea of when I would be able to obtain more. 4 miles later that problem solved itself as I entered an oasis village in the dead of the night. I felt like I was trespassing. All of the buildings were totally silent and dark, enterances fortified with gates and steel doors. I wondered what it would be like to be inside, protected, comfortable, and asleep. I wondered if anyone were awake and I would be considered welcome or unwelcome if spotted.

I heard the sound of running water and saw a headlight. Another racer, Carlos Mazón, was refueling his own bottles.

“It’s good water” he said. “I didn’t even need to filter it”.

I wasn’t taking chances. I tossed in some purification tablets into freshly filled bottles and my hydration pack as I emptied the last half bottle of pure water that I had down my dusty throat. Carlos left before I did.

I remounted quenched of thirst but as another set of steep switchbacks threaded its way through the village I realized my legs had all but abandoned ship. I couldn’t pedal up the climb. Was it the long miles? Was it the poor nutrition? Was it the sleep deprivation or dehydration? It didn’t matter. I was spent. For hours I had been spotting into the darkness fantasizing about the place that I would stop for the night, but never having bikepacked before left me with an unsure feeling about what exactly constituted a proper place to stop and sleep. There were no hotels to be found. There were no campsites. There was mostly only endless rolling hills made of tumbled rock or eroding cliffs. Not finding anywhere to stop simply meant that I needed to keep going which I had done until I reached this moment. I couldn’t continue on for much longer. I very seriously needed to stop and sleep.

At the summit of the hill my small hike a bike ended. Exited the village and as I did a four wheel drive police truck spotted me and roared to life. The police had been fantastic all day. Would this one keep the streak alive or menace me for passing uninvited through this remote village? The truck pulled out in front of me, headlights blazing. With nothing else to do I kept riding directly behind it directly into the cloud of fine dust that it was kicking up. I choked on diesel fumes and dirt. My uninvited lead car chaperoned me out of the town and into the blackness once again. It drove so slow that I wanted to go around but thought that might be a bad idea. The choking continued. This was an unsustainable arrangement of police truck and bicycle rider. I decided to slowly make distance between myself and the truck by easing up on my pace. The police would have no idea what the proper speed of a bicycle is and would assume that they had dropped me. After a few minutes I began to breathe clean air again. But between the hike a bike and the police truck dust storm I had hit my wall. It was imperative that I stop for the night and it quite honestly didn’t matter where I stopped anymore as long as I could find something, anything that seemed slightly out of the way of the road and the prying eyes that passed along it.

And then it appeared to my left: A thicket of trees no more than 8 feet high was growing in a dry river bed not far from a small eroded hillside. As soon as I saw the thicket I new that this is where I was going to stop and rest. As tired as I was something inside of me fought as I came to a stop.

“This is a race Stephen, what are you doing? How can you stop? You must GO! You must continue”

I shut that voice up. I was finally tired enough to stop being a bike racer insecure about being caught. I was finally tired enough to start thinking smartly about what my body was really capable of, or in this case incapable of. It was time to rest. The fight was over.

The thicket of trees blocked the view of the road for me. I felt hidden. At first I planned on hiding inside of the thicket for extra security but as I plunged into it I was soon pierced by a half dozen 1″ thorns and quickly retreated. Of course this wasn’t a lush thicket, this was a nasty barbed desert thicket. Those trees had fought hard to even exist in this impossible desert environment and there is no way in hell they were going to roll out the welcome mat for hungry goat, camel, donkey, or a tired bike racer.

So I slept NEXT to the thicket not in it. I rolled out my tent but pitched no poles. I treated it light a bivvy sack. I inflated my sleeping pad and wondered how long it would last next to all those barbs and thorns. I stripped naked and stood there in the night for half a moment while a breeze swept away the last of the day’s sweat. I pulled on some fleecy pants and a teeshirt.

I laid down and picked up my Garmin Inreach tracker and sent a message to both the race organizers and my wife. “All is well, taking a break” was the pre-composed message that went out.

Little did I know that my wife and kids were tracking me on the race map at exactly that moment. On her glowing phone screen she could zoom in on my dot on the map on the other side of the world and she could see the EXACT tree that I was now sleeping under. What a crazy world we live in.

My InReach beeped and lit up.

“I see you. I love you. Rest well.” came her response on the tiny screen.

It was nearly 2am. With that I closed my eyes and drifted off quickly. Sleep was not difficult to come by once I finally surrendered to it.

The only sounds that interrupted me for the next four hours were the sound of bicycle tires grinding tiny pebbles on the road 30 feet away from me. Those were the sounds of other racers, those stronger or more stubborn than myself passing in the night.

2:00am. 132 miles covered. Approx 20,000 feet climbed. This concludes my first day of Atlas Mountain Race 2020. The world may have moved on but I feel like I can remember every bit of it.

2 Comments

Where can I find chapter 2? This feels like a cliffhanger ;-)

I haven’t written it yet. It took so much to write this chapter and I haven’t been able to find a few days to stop and write up the next one. But I hope to!