We are only days from the end of 2015 and there are a bunch of highlights from the year that I haven’t had the time to share. I doubt I’ll get to everything on my list and I won’t be able to cover them in much depth, but I’d love to leave them on the journal for the sake of posterity.

The first of these highlights is the Dirty Kanza 200, the two hundred mile gravel (and in our case mud) race through the roads and hills surrounding Emporia, Kansas. There is no way for me to write up this particular event quickly, so if you continue reading please remember to eat often and stay hydrated.

Rodeo cobbled together a solid crew for the race. Tom Miller, Derek Murrow, Chris Magnotta, Patrick Charles, and myself made the drive 10-ish drive out from Denver, CO for the event. O.G. Rodeoer Michael Tam also met up with us in Kansas. Michael races for another team now but he’ll always be a part of our extended family.

Dirty Kanza isn’t an incredibly long running event, having been founded in 2006. The combination of grueling roads, epic distance, and sometimes ridiculous weather conditions conspired to quickly give the event prominence and the rise of gravel riding culture in general continue to fuel its growth. In addition to those factors I also need to give a shout to the host town of Emporia, Kansas which has completely embraced the event and created an incredibly friendly supportive culture for the race to grow in.

None of the guys on our squad had ever done DK before. We didn’t embark on a dedicated training plan in order to prepare for the rigors of the race, but we may or may not have exceeded our monthly data allowances while Googling and trying to determine exactly which tire was best suited from the course. It was difficult to exactly discern just exactly how harsh the course would be on our tires and other equipment. Would the roads be simple mild dirt and gravel or, as some bloggers put it, “200 miles of riding on shards of broken tile”? I think in retrospect the answer to that question is relative to whatever conditions you normally ride in. If all you are accustomed to riding is pavement then the DK200 course conditions are brutal and hellacious, but if you ride gravel or dirt with reasonable frequency then the course isn’t exceptionally bad at all, and you’ve probably seen it all before.

We ended up with five very different bikes on race day. General equipment (from memory) was as follows.

- Derek with a 29″ MTB on a rigid fork and small-ish 1.9″ tires.

- Patrick on a Kona CX bike on some variant of Bontrager file tread tubeless CX tires.

- Tom on a Salsa Warbird on Specialized Trigger tires. Can’t remember if he was tubeless or not.

- Chris on his Traildonkey 1.0 on some Panaracer Pasela 38mm PT slicks. Yes, slicks. More on that later.

- Me on my Traildonkey 1.0 on WTB Cross Boss 35mm tubeless tires.

Looking back on the race months and months later, it strikes me that tire and gear selection weren’t the biggest factors in DK this year. This year the race was defined ENTIRELY by the elements, and by elements I mean mud. It was a very wet spring in Kansas this year and on race day we woke to a wet drizzle falling on an course that contained a half dozen river crossings above flood stage. The venerated Kansas flint that was so tough on tires and riders took a back seat to the even more brutal Kansas mud which eviscerated the entire race. I’m not sure if anyone truly had any idea what they were in for at this year’s event.

In the early hours of the day, at the starting line, and in those first half dozen miles spirits were very high in our group and the larger crowd. The buzz and energy in the air at the starting line was fantastic. Smiles were a dime a dozen, whoops filled the air, hugs with support crews and family were exchanged.

The gun went off and we hurtled down the road in the damp morning light. Within a mile or two we turned into the dirt for the first time and immediately the elements began to show their face. Not 200 feet into the first gravel sector a rider hit the deck in a puddle. A couple hundred feet later I noticed someone else to my left in the grass fiddling with their drive train, limp derailleur in hand. Still, those early casualties seemed minor. For the most part the group hurtled down the road at a great clip. For Rodeo our plan was to stick together, pace ourselves, and not get blown up early in the race. In a 200 mile event there aren’t many riders who know how their bodies would handle the distance, ours included. The safe strategy is to ride well below your threshold and leave a lot in the tank because it was going to be a long, long, long day in the saddle.

At about mile six reality hit like a brick wall. As I cruised down the road at a pace much higher than I should have been riding, I thought to myself that this was shaping up to be an awesome day on the bike. Up ahead I noticed increased congestion on he horizon. Riders were slowing down. Riders were walking. In my ignorance I thought I had stumbled on a group of riders not skilled in mud riding. Not so. What I had stumbled upon was the first of a half dozen of the soul crushing mud bogs that the course contained that day. This wasn’t mud that you could ride through. Those who tried mostly failed and for many unlucky riders the resulting clogged drivetrains resulted in derailleurs seized and snapped from frames. I passed more than a couple dozen riders throughout the day silently walking along the course, chains limp, bikes stricken with a fatal blow that could not be repaired. As I passed these riders turned walkers I thought of what it must feel like to prepare for this event for so many months and at significant expense only to have the day cut so unfairly short. Another cold reality set in: This fate was doled out randomly. Any rider of any ability could at any time be pedaling only to find themselves unceremoniously removed from the race with a mud induced equipment failure.

I pressed on, mostly on foot. As I looked at my feet I couldn’t recognize them. The mud was so thick and sticky that it replaced my slim shoes with giant moon boots made of mud and weighing about 10 pounds each. Slowly I adapted to these conditions by climbing the grassy bank on the side of the road and walking through the weeds. The going was very very slow and disheartening, but at least progress was made.

These conditions continued on for a long while. In my mind I whined to myself that this wasn’t what I had signed up for, a hiking race through Kansas mud. If these conditions persisted it was obvious that nobody was going to complete DK200 this year. A pace of one or two miles per hour made a finish impossible. I wondered to myself at what point I would give up and quit. It seemed the inevitable outcome for everybody. I continued on not because I was some sort of strong willed rider, but because there was nowhere to really quit the race. The DK200 course weaves through hundreds of miles of pretty much nothing but beautiful, remote Flint Hills. You can’t pull over and jump in the sag wagon. There is no sag wagon. You might be able to call your team support car to pick you up, but as a T-Mobile subscriber I knew that rescue was not a call away. T-Mobile had barely worked since leaving the Denver Metro Area two days before.

A photo posted by patrick charles (@pchuckogram) on

So on I pushed through the mud. Sometimes alone and sometimes with fellow riders. Somehow the Rodeo team plan of staying together had blown up mere miles into the race. I hadn’t seen my team mates for hours and indeed never again saw any of them before the finish line. Eventually, as suddenly as it had started the mud relented and was replaced by wet but firm ground on which to ride. I carved the mud from my wheels and frame with an improvised Park cassette brush/scraper and when things began to once again spin freely I remounted my Donkey and continued on my way.

Over the next 20-30 miles everything was a bit of a surreal dream. The Flint Hills were draped in a heavy fog. They were beautiful. I didn’t really have a sense of going fast or slow and I didn’t really care much about my speed except for wanting to keep pace with companions on the road that I picked up throughout the day. It was a disappointment to have lost my team mates early in the day, but not having a group to call my own meant that I was more free to strike up conversations with strangers that happened to share my pace. I really enjoyed these chance meetings. Some lasted only a half mile or less, and some shared the road with me for hours throughout the day.

On the second or third mud bog of the day a strange thing happened. The mud collected so densely in my front fork that nothing could pass through. A single rock in particular stuck in the goop and slowly started cutting away at my sidewall while I continued on in ignorance. Eventually that rock chewed its way through my (tubeless) tire and it quickly went flat. I was pretty devastated. In retrospect I’m not exactly sure why I felt this way. Anyone doing Dirty Kanza should plan on not getting any number of flats throughout the day. It isn’t really a question of if you will flat but more a question of how many times you will flat.

I had flatted in a pretty bad spot, in that mud bog. A flat tire should be a five minute setback, maximum. I changed the flat quickly but in the process a bunch of mud and rock almost inevitably contaminated the tire and tube. When I reinflated with a C02 canister only a second hand passed before a new rock, having snuck into the tire with the mud, punctured the new tube.

(Insert weeping and nashing of teeth)

I removed the now flat 2nd tube and this time tried to rinse the whole mess out with energy drink. My second C02 was faulty so I tried to use my backup pump to reinflate. I quickly discovered that my pump was not only covered in mud, but the mud had contaminated the pump itself and made it nearly impossible to operate.

My five minute tire changed ended up lasting the better part of a half hour. I stood in that mud bog huffing, puffing, swearing, and cursing my pathetic luck as riders passed one by one. Some made eye contact as they rode by, some gave me a knowing nod, some stared into the empty infinity of the course before them, not wanting to waste precious energy inquiring about my fate.

Riding DK 200 seems to me a bit like climbing Mt. Everest. If something goes wrong in the Death Zone the odds are that nobody is going to save you. It had never really made much sense to me how you could leave a dying climber behind as you sought the summit of the peak but as I stood there on the side of the road I felt no anger towards those who now rode by without slowing. Every rider had already suffered SO much to get this far, only roughly thirty miles into the race, and each rider still faced another one hundred and seventy miles of unknown suffering and misery. Sympathy for a fallen rider wasn’t a luxury that many could afford themselves that day.

When my tire was once again successfully remounted my morale was at the bottom of a deep pit. Before the flat I had been making surprisingly good headway in the race. My goal for the event was to place in the top 150 out of the roughly 900 starters and I seemed to be on pace to accomplish that. With my setback I was now sure that I’d slipped far back into the field and more importantly it seemed that the fight to get the tire back on had exhausted and demoralized me to such a degree that I didn’t really care much about whatever else happened that day.

Once again there wasn’t really an option but to get back on the bike and keep pedaling, so pedal I did. Beyond the frustration of the flat, another feeling crept in. Now that I’d had a bit of a disaster I was less concerned about my result in the race. A good result seemed improbable so I was now emancipated from having to aspire to that. I felt a bit liberated. All I needed to think about now was riding my bike as well as I reasonably could and finishing with whatever dignity I could salvage.

For the next 40 or 50 miles I simply rode my bike. I didn’t race, I didn’t think a lot, I just rode and rode and rode. Conditions on the course improved, my nutrition was doing its job, and I began to really enjoy myself. Stress in a race is a great motivator for success and results but it can really rob you of the inherent joy of just riding a bike. Now that the race is months behind me I can safely say that I’m glad I got that flat at Dirty Kanza because it changed my approach to the race and got my mind a bit more right, a bit closer to what I love about bikes and racing.

Another funny thing happened in those 50 miles after the flat: I passed a LOT of people. At the time I wasn’t counting because it wasn’t very important to me what place I was in, but I did notice that exactly zero people passed me and stayed ahead between when I got the flat and when I arrived in the first support stop at roughly mile 80.

As I neared the support area I reminded myself of my overall DK race strategy: Never, ever, ever stop for any reason that isn’t absolutely necessary and even then never stop longer than is absolutely necessary. For many people the support areas and pit stops along the DK course are an excuse to get off the bike, get comfortable, get refueled, and collect themselves before continuing on the course. For me rest stops are just the opposite: They are scary, intoxicating tricks meant to suck riders in and never let them leave. Rest stops are evil because of the temptation that they contain. You can roll into a rest stop and easily give away 15-30 minutes while you wonder around, drunk on the feeling of not being on the bike. Your support crew just makes it worse. They offer you a chair, ask you if you need dry socks. They feed you and massage you. All the while precious minutes tick by, minutes that are impossible to gain back out on the course. My strategy was to resist the temptation of the rest stop and power through before they robbed me of precious time that I’d work so hard to gain through every pedal stroke and act of will I’d committed that day.

I executed my rest stop strategy to perfection. I sped into the stop with a half dozen other riders, dismounted, grabbed a few bottles and bars, lubed my desperately dry chain, and charged back out onto the course. Somewhere in the middle of all of that I heard someone yell something funny to me:

“You’re in seventeenth!”

I’m in seventeenth. What does that mean? Seventeenth is a number? Did I take seventeen minutes in the pit stop? What is the significance of seventeen. Wait a minute….

AM I IN SEVENTEENTH PLACE!?!?!

I was in 17th place in the entire race. This didn’t register at first, and then it did. When it did I completely freaked out. I was in 17th place in the Dirty Freaking Kanza! I didn’t know how, it didn’t seem possible, but I’d heard it right and it was true. Despite the flat tire I was somehow having a ride of my life that I didn’t even know that I was capable of.

This bit of info electrified me and lit a fire under me. I charged out of the rest stop, out of town, and back onto the course. I sighted riders on the horizon in front of me and hunted them down. 17th, 16th, 15th… 10th, 9th. I was working my way up the leaderboard in a hurry…

… until I hit the next mud bog.

The fourth or fifth mud bog (depending on how you are counting) of the DK200 was not the longest of the day, but it was probably the worst. By that point we were about a hundred miles onto the course and already very very tired. I was charged by being so high up the leaderboard but it took only fifty feet of deep mud to burst that balloon. The one thing I haven’t mentioned about DK mud is that it isn’t fair mud. For whatever reason it doesn’t treat every rider equally. Some riders are slowed to a stop with bikes covered in 40 pounds of the stuff. Some bikes are literally torn apart by the powerful rider combating insane amounts of drag caused by the stuff. And then there are the riders that seem to take a lucky line and experience almost no mud drama at all. In the fifth mud bog, which was about a mile long, it seemed like I was the guy stuck with the 50 pound bike. I traversed it mostly on foot while other riders seemed to ride right by me. This was extremely frustrating to watch. I wasn’t the only rider experiencing this. The bog was dotted with riders like me who were stuck with cranks, brakes, and wheels that wouldn’t move.

The bog was L shaped and when I turned left I could see the end of it about a quarter mile in front of me. At the end I could also see riders remounting their bikes and pedaling at speed over the next ridge. In life in general I have an emotional aversion to being left behind, so this situation triggered a bit of a panic for me. being stuck in the mud and watching a dotted row of riders disappearing in the distance was pure hell.

Hell eventually ended though and I made it to the end of the mud. I tried to use my tool and a stick to clear my frame again and start my wheels spinning but it seemed to have no effect. I couldn’t get my bike going again. Around me were a dozen other riders with a similar problem. All at once somebody had a genius idea and bolted for the ditch which was filled with water. Quickly other riders followed and a cluster of us were soon seen thrashing in knee high water while we furiously washed our bikes and freed them from their mummified state. Soon we were all back in business, and our bikes were pretty clean as well! What a massive transformation that was both mechanically and in terms of mood.

Once again I set about making up for the time that I lost in the bog. I guessed that about 10 to 20 riders had passed me and I had a lot of work to do. Over the next 20 or 30 miles I leapfrogged my way back up the leaderboard. My strategy was to ride with a rider or group of riders for a while, trade pulls, and then when I felt good I launched up the road towards the next rider or group of riders that I could see.

This approach worked well and by the second neutral support stop I was more or less back in business. The second neutral support stop was also when the wheels more or less came off my wagon and my ride turned from race to struggle for survival.

My biggest error in the DK200 wasn’t a mechanical one, it was a nutrition error. Based on some previous adventure racing experience I planned on trying to intake most of my calories through liquid, not solids. My utterly simplistic approach to this was to carry electorlyte water in my backpack for strict hydration and very thick calorie drink in my bottles for energy replenishment. Before the 130 mile mark of the race I ate zero solid foods and I experienced zero peaks or valleys in my energy supply. Even if some people would argue that the science of my approach was flawed, it worked absolutely perfectly… until the point that I ran out of energy drink. In my rushed race prep that morning I had left the canister of sports drink powder in my hotel and after I used up my pre-prepped bottle resupply from the first support stop I was out of luck. Mile 130 was when that happened.

After mile 130 everything went downhill for me. At first I felt okay eating solid food but I had a strong sense that I wasn’t refueling as quickly as I was burning energy. Even in a good race nutrition scenario the body can’t replenish calories as quickly as it burns them, but after my liqid superfood ran out my rate of calorie replenishment fell off a cliff. During those miles I was riding with two other riders, a singlespeeder from Chicago and a CX pro from Boo Cycles. We traded equal pulls as the miles passed and I worked hard to conceal my faded energy as much as possible. If they were to drop me I’d be on my own in the Kansas wind, but with them I was making terrific headway. I tried various things to incentivize us staying together. I shared my food and chain lube, and, it turns out my GPS as well because Mr. CX pro didn’t have a map or a GPS with him. It occurred to me that he was much much faster than the other two of us but he simply didn’t know where to ride, so he was more or less stuck riding with us.

Our group arrived together at the final pit stop, some 40 miles from the finish. I was in a horrible state but a calorie resupply would hopefully solve that. In a bit of a bonk induced panic I was unable to find my support crew, so I begged some coke and bars off of another team and hit the road again in a hurry. I was on my own until a chance train crossing halted me for ten minutes. Two other riders joined me. One was the singlespeeder that I had covered many miles with, and the other was a racer I’d traded many pulls with at various points in the race and who had himself been running as high as 4th place until fate smote him repeatedly. Kanza giveth, Kanza taketh away.

The pull of the finish was strong in those last forty miles. Road conditions were excellent, temperatures were good, and our group worked pretty well together. My fading energy left me as the weakest rider in the bunch but I once again dug as deeply as I could in order to again take advantage of the strength of the group against the now relentless wind. My stomach had long since gone on strike and it seemed that I simply wasn’t processing food anymore, but I lectured myself out loud that I must keep putting food in my mouth and swallowing it. To finish 180 miles of Dirty Kanza only to completely mess up the final 20 miles would be a pretty big tragedy for me, so I focused on trying to continue to eat, drink, and practice mind over matter.

It us funny how an an average day a 20 mile ride is unremarkable, but when you’ve ridden yourself past empty 20 miles feel infinite. I tried over the course of the race to not look much at my mileage tally, I tried to ignore how far I had to go. In those final 20 miles I broke that rule and stared at my GPS almost non-stop, trying to will the miles by faster and faster. 181.1, 181.2, 181.3. My slow progress seemed excruciating.

The strongest man in our trio had since dropped the other two of us. He pushed on alone and for his efforts he was rewarded with a category win in the DK. It was only later that I learned that he and I were in the same category. My remaining companion with his single speed was my life line in those final miles. While I grew more and more hollow and silent he picked up the slack in our conversation and kept talking to keep things lively. I was thankful for his efforts and self conscious that most of my conversational contributions consisted of a single word.

In the final mile to the finish we passed through the university campus. My wheel mate finally detached from may pace and pulled away. I’m glad he finished in front of me because he was stronger in those final miles. I certainly didn’t deserve to finish ahead of him. I zig zagged left and right until I turned onto the final finishing straightaway through downtown Emporia. I could hear the announcer, feel the music, and see the huge crowd waiting for us. The crowd wasn’t only full of friends and family of the racers, it was full of the citizens of the town. Dirty Kanza is a massive spectacle for Emporia and it seemed that the whole city turned out to genuinely cheer for racers as they finished. Emporia really appreciates this race and the racers, and you can feel the genuineness of the crowd as they cheer you down that final tunnel to the finishing banner.

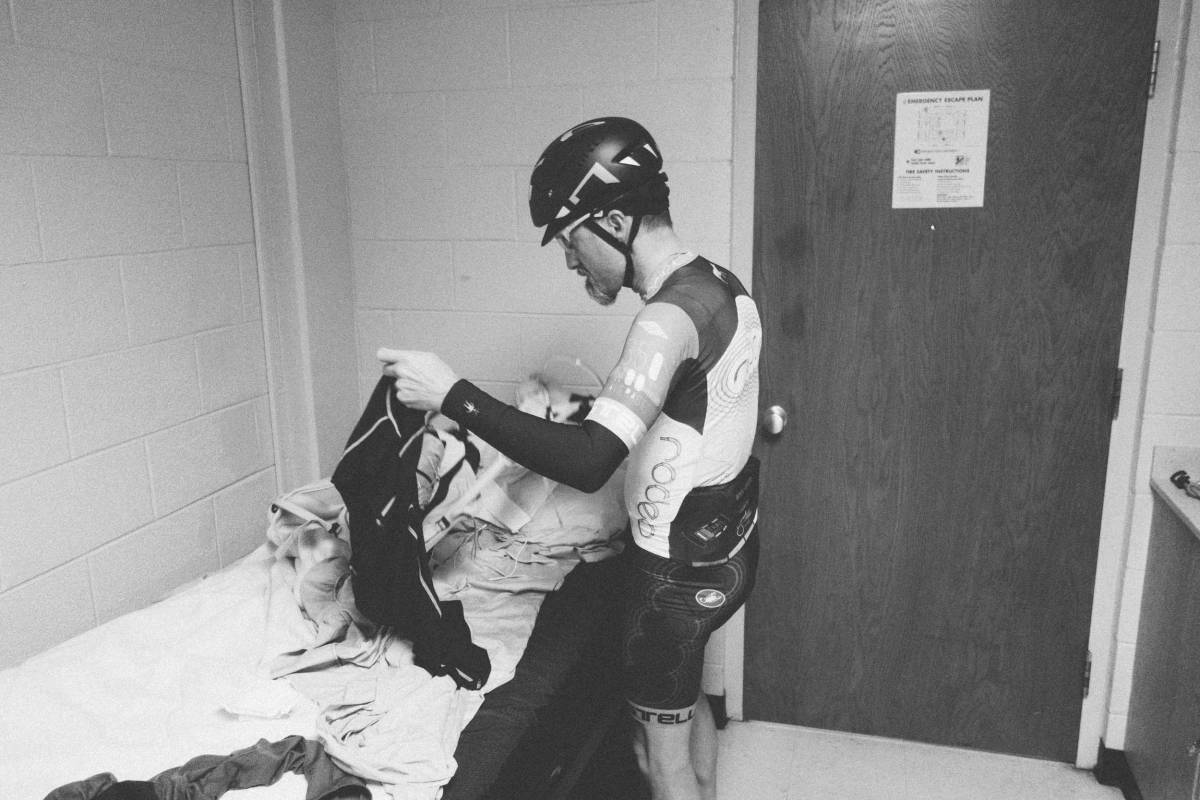

There are a number of races that I’ve done in my life where I’ve teared up at the finish. The races where it happens are the races that I’ve dug deeper than any other. They are races where I’ve barely held back the dam of fatigue, pain, and emotional exhaustion of the event. When I cross the finish line at those races the dam brakes and the enormous difficulty of what I’d just done is finally allowed to flow freely. It is overwhelming. I was overwhelmed when I finished the Dirty Kanza 200. I had to be helped, peeled off of my bike. My balance was off and I could barely stand. I didn’t know what to do with myself at that point. My thoughts turned to my team mates. I didn’t see any of them around so they must still be out there? I couldn’t imagine still being out there, still pedaling.

People often describe having nothing left and I think that sometimes the figure of speech is used too freely. It has become cheapened. DK200 is the only time in my life where I think I really truly had nothing left. The degree to which my body stopped working exactly when I crossed the finish line was incredible. I wanted to wash off my bike, to eat, to do the things you usually do when you finish but I could barely function. I found a jar of pickles on a random table and started eating them one after another? Each pickle was a burst of heaven, a rush of salt and vinegar that shocked my senses and reminded me that I was awake, that I wasn’t dreaming, that the race was over. I ate 3/4 of the jar before it dawned on me that a belly that was completely empty save for pickles might not be that healthy. I found a wall out of the way of the commotion of the crowd and sat down. I meant to just gather myself and get back up but instead I blacked out. I didn’t just fall asleep, I fell off of the face of the planet. I entered a black hole where light and sound couldn’t escape. I don’t remember any of it.

I woke up 40 minutes later. It was darker, I was disoriented. Someone helped me to my feet and I waddled over to the finish only to see that Chris had just crossed the line. It was a beautiful thing. He looked absolutely horrible. He had ridden all of those miles, muddly and dry, on 38mm slicks. Slicks would have been an ace selection in dry conditions, but in the DK mud they were horrifyingly unable to provide traction or steering. Still, Chris was one of the few people that finished the race before sun down that day. Chris is amazing.

Later that night Tom, Patrick, and Derek also finished the DK200. In a race where the lowest finishing rate was 19% and the highest ever was 70%, 100% of our Rodeo Adventure Labs crew finished the event. After the early miles none of us ever saw each other on the road. We all overcame gear problems, mud problems, tire problems, food problems, and any other kind of problem you can imagine. Each rider had such a different day, such a different story. I could never attempt to tell them all. Indeed, I was so mentally drained after the race that I never got around to trying to write any of this up until now, mere days before the end of the year.

The drive back to Denver passed a lot quicker than the drive out to Emporia. The miles were filled with stories from the race and the comparing of experiences that we’d all had. There are too many stories to tell here. Too many to remember even. If my recounting is already this long, consider that the other 900 riders out there that day each had equally epic stories of their own.

One of my favorite post race recollections was from Patrick. He told me that after he got through the final bad mud bog the course turned right. As he cleaned off his bike he notices a long stream of riders turning to the left and riding down the road in the opposite direction. “They are going the wrong way” he said. “No, they’re quitting” was the response. I’m sure it was an incredibly difficult decision to quit at mile 100 like that, but not as difficult as it was to saddle back up and chose to ride another one hundred miles into the unknown.

Never have I ridden in anything like DK200. I’ve done Leadville, I’ve done 150 mile epics, I’ve done 50 hour non stop adventure races but none of them was as difficult or beautiful to complete. DK may be a timed event but it really isn’t a bike race in my opinion. DK200 is mostly a competition that each rider has with them self. Some riders are beaten by themselves, some triumph over themselves.

Yes, they hand out trophies and times at the end of Dirty Kanza but everyone who pushes through the beauty and wrath of the Flint Hills can be equally proud of their efforts. There truly isn’t one effort more impressive than the next, and indeed those who are out on the course longer can arguably be said to have prevailed against more adversity than those that finish the course quickly.

I swore to myself that the finish line that I’d never do DK again, but if you see people lined up at the starting line of Emporia, Kansas in Rodeo kits in 2016, there is a good chance one of them will be me.

Tom Miller – 10th in category, 71st overall

Chris Magnotta – 7th in category, 57th overall

Patrick Charles – 27th in category, 150th overall

Derek Murrow – 19th in category, 201st overall

Stephen Fitzgerald – 2nd in category, 14th overall

Michael Tam – 12th in category, 99th overall

1 Comments

Beautiful write-up. I just turned 50 this year and I’m training to participate in my first Dirty Kanza. Thanks for the inspiration!