Tom Haines

The beauty of things gone wrong

- ,

- , Adventures

On a 2,588-mile bikepacking adventure, the worst moments can become the best

I, a 56-year-old man with a belly full of lamb kebab and french fries, woke at 3 am to find my left eye swollen shut. The dead-of-night swelling, I knew right away, must have come from the bad bee sting the afternoon before. That sting, on my left eyebrow, had happened as I rode a fully loaded bicycle another 130 miles on day two of North Cape 4000, an unlikely adventure across Europe, during which I hoped to ride more than 2500 miles in 20 days, ending at the Arctic Ocean. Such a challenge was new to me, and I’d spent the previous six months getting ready – training and nutrition, gear and pacing strategy. So, in the dark of the hotel room an hour north of Munich, as the swollen eye threatened forward progress, I felt panic. Would the eye open again? That was likely. The real question: When?

I bolted up and into the room, bumping past the bike leaning against the wall, opening the bag strapped to the seat post, digging for the first aid kit. I could see with my right eye, and with that I found the small packet with two antihistamine tablets, took them, and propped myself up in bed, hoping that would help the swelling, too. Hours later, no luck. I used my good eye to Google for a nearby pharmacy, which opened at 8, and there a young pharmacist proclaimed, in perfect English, “You really ought to see a doctor.” But I still felt a powerful urgency not to lose even a few hours of forward movement. I asked the pharmacist for the strongest antihistamine he could sell me. I swallowed two of those and pedaled tentatively beneath a steady rain through the center of town.

It is hard to ride a bike with one eye, and I felt vulnerable, as though even the slightest bump in the road, unseen, might launch me over the handlebars. As I rejoined the North Cape route into the rolling fields and forest of Bavaria, I began to accept that I could not push against the limits of my eye. So, I went slower. And as I did, that dose of one-eyed uncertainty, so early in such an overwhelmingly long adventure, delivered another unexpected thing: a sense of calm.

So much of long-distance bikepacking far from home, it had seemed to me, was about control, everything orchestrated toward reaching the destination. Yet, in that first hour of riding with the swollen eye, I realized I didn’t care so much if I made it to the northern edge of Europe. My mood changed from panic about the eye to satisfaction just to be riding a bike on a rainy day. Each pedal stroke became not a guarantee of arrival, in other words, but a chance to be exactly where I was. And I understood, deeply and for the first time since I decided to ride North Cape 4000 so many months before, that the doing, more than the completing, was the point.

If this seems an obvious epiphany, it’s important to understand that, in signing up for the race, I was entering unfamiliar terrain. I’d been a bad adolescent athlete and only began to find my footing as a middle-aged trail runner. A decade ago, my then-13-year-old son got the biking bug, and that prompted me to dust off my aluminum road bike with rim brakes and mechanical shifting. I rode with him year after year, through group rides and cyclocross races and, eventually, on an ambitious bikepacking trip, our first, into the Andes. My son kept accelerating toward collegiate road racing, and I eventually realized that he’d made me a cyclist, too.

Then, when a divorce opened my life, I decided that I wanted a particularly solitary challenge and chose the North Cape 4000. Nothing like long days in the saddle, I figured, to set my head right. At the start in Rovereto, Italy, last July (this year’s event kicks off this week), we were 450 cyclists from 43 countries. The organizers provided a GPS track of the route north. But in every other way, the ride was unsupported. Each person was responsible for carrying their own food and shelter, handling bike repairs and managing physical and mental health. North Cape 4000, the organizers say, is an adventure, not a race. Yet official finishers must arrive in 22 days, an average of more than 120 miles a day. So, while I was only ever planning to race myself, there was in that challenge a constantly ticking clock: I’d set a personal goal of arriving at the bluff overlooking the Arctic in 20 days.

And there I was, with that one good eye heading north into a rural stretch of Bavaria, when I heard from behind me the greeting, in French, of Alexis, a young guy I’d ridden with up and over the Brenner Pass from Italy into Austria two days earlier. He slowed his pace, to match mine, and we stopped for a coffee and calories at a gas station. Alexis powered on, and I pedaled gingerly into the afternoon, as the sky, and my eye, began to clear. Before I’d set out, I’d asked a friend back home with far more long-distance cycling experience than me for advice, and he’d said, “Take care of the little problems before they become big problems.”

That helped me to keep perspective, a sense that even my injured eye was, at this point, a relatively little problem, and I had an opportunity to keep it from becoming bigger. So, by late afternoon and with the eye nearly open, I stopped for the day, hoping that a good night of rest could help it heal fully. The next morning when I woke from sleep buffered by more antihistamine, the eye was a bit puffy and itchy, but that is all.

In an event like the North Cape 4000, each rider sets their own rhythm, and just like that I was back to mine: beginning each day by 7 a.m., moving for 12 hours or more before settling for sleep. I had set up my Trail Donkey 4.0 for the road, with Shimano 11-speed drive train and 32-millimeter road tires. I carried with me a sleeping bag and bivy, but I chose to save that for the Arctic north. That first week, rolling between nestled villages in lower Europe, I aimed each night for at least six hours of quality sleep, indoors and off the ground.

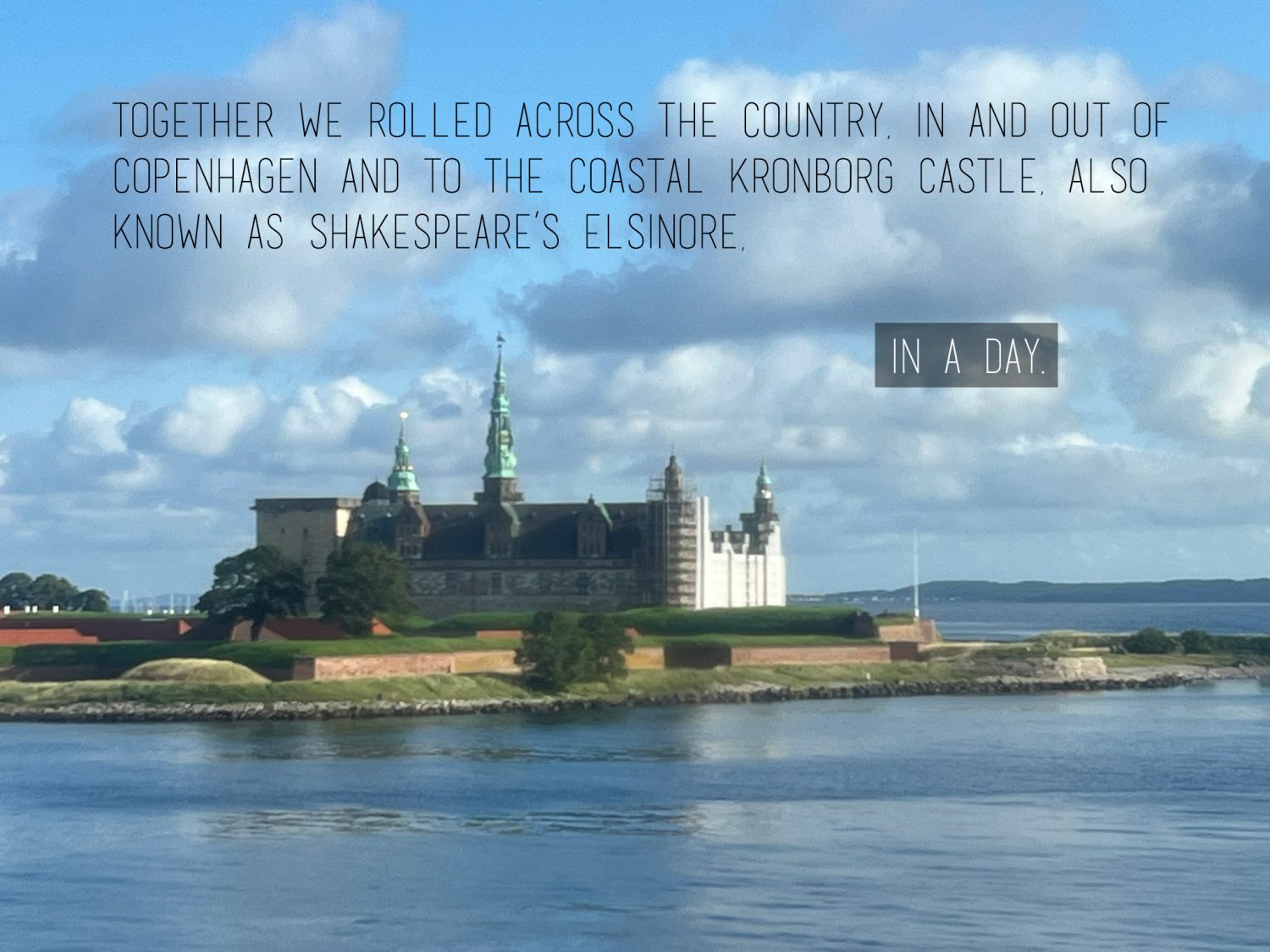

So, with nightly rest and careful, constant fueling – as anyone who has done long-distance endurance events learns, such things are most about being able to eat, and eat, and eat – I found myself clipping along through that first week and into the second. (Don’t get me wrong, my 20-day pace was by some measures plodding; the first two riders to arrive at North Cape last year did it in 10 days.) Still, for me, the glorious, full-sun gusts of the Austrian Alps had so swiftly given way to the weaving lanes of Bavaria, which led to a route into and out of the Czech Republic, then into and out of the center of Berlin, and on to the Baltic Sea. I found in those days a familiar group of riders – Robert, from Poland, Verena, from Germany, Florence, from France, and more – with each of us leap frogging one another along the way. While waiting for the ferry to Denmark, I met Martin, a young guy from Slovakia. Together we rolled across the country, in and out of Copenhagen and to the coastal Kronborg Castle, also known as Shakespeare’s Elsinore, in a day.

I say all this just to be clear that there was so much that seemed easy and good, and that after ten days the swollen eye seemed surprisingly distant. The ride, mostly, was just plain fun. Yet, I realized that the early lesson the swollen eye had taught, and the strength it gave me to accept adversity and focus in the moment, was good preparation for what could come next. Because the ferry that delivered me from Denmark to Sweden marked the beginning of a more solitary stage, with long days on remote roads passing from forest to lake to field. Villages were farther apart, with fewer people met along the way. The ride shifted from a daily dance of distractions to a long, steady grind through the center of Sweden. At first, I embraced solitude, as that’s why I’d come in the first place. But each day brought soft, steady rain and light headwind from the northeast, the direction the route followed toward the Arctic Circle. I was building self-reliance, but also an awareness that all that I did would depend on my alertness.

Late one morning, I stopped in a bike shop in a small city to service the brake pads and chain, which already had more than fifteen hundred miles of hilly wear and tear. The delay meant that I set into the bulk of the day’s miles at mid-afternoon. That far north in early August, the sun stays up until 11 p.m. So, in early evening, with more than 130 miles ridden, I chose to go up and over a 14-mile climb and 20 miles to the next town.

After 30 minutes, clouds that had been thickening delivered a steady rain and a deepening dusk. I’d been eating regularly throughout the day, but for the first time since Rovereto, I began to bonk, deeply. The physical emptiness triggered an emotional one, too. And as I arrived near the top of the climb, I didn’t know if I could continue.

By now it was after 10 p.m. I stalled on the roadside. I eyed the mossy forest and thought about crawling into my bivy sack beneath a canopy of evergreen. But I worried that, already wet and with the wind picking up, I could be ill-prepared for a long night on the ground. So, like that night in the hotel north of Munich, I found myself fumbling through the saddle bag, this time for another layer against the rain. I realized my day may be done, that I was unlikely to ride further, and that brought a kind of release, a deeper settling into the experience of moving across a continent under my own power.

When I lifted my head and looked back down the road, I saw, in the grey mist, the mildly bobbing beams of two white bicycle headlights. Immediately, I felt a surge of strength, and I hustled to buckle my bag and swing a leg over the bike before the two riders arrived, echoing warm greetings and offering big smiles. These guys, who I learned were named Ron and Nic and had come all the way to the Swedish forest from the busy streets of Manila, barely broke pace but swept me up in their energy.

Nic often stayed 20 or 30 feet behind Ron, and later he would show me a video he took of Ron and me, side by side, chatting as our legs spun smoothly. Ron had been telling me about Everesting attempts with Nic and other cycling buddies on a big climb outside of Manila. My body language in the video is steady and relaxed. I look not as though I were in the depths of a dark moment, but out for a coffee ride on a soggy Sunday.

The three of us continued into the dark and on to the town of Örnsköldsvik, where we arrived at Max Burgers five minutes before its midnight closing. Ron, Nic and I were soaking wet. But calories counted more than comfort, so we sat in slippery plastic seats and devoured burgers and fries, a big green salad and thick shakes. Between bites, I told them about the low point at which they’d found me, empty and defeated within myself, trying to accept the hard moment on that roadside when they had rolled up. I explained how much it helped to have their company. Ron gave a staccato laugh as he reiterated the importance of the lesson I’d learned with that swollen eye more than a week before: focus in the moment and accept where you find yourself. Move forward from there. As for the thousand miles ahead, which would cross the Arctic Circle and trace the shore of the Barents Sea, Ron said, simply: “Our bodies have adapted. Now is just to manage.”

Luckily for me, after that dark hilltop evening, the weather shifted, bringing a steady string of warm-air, blue-sky days with a sturdy tailwind from the south. I was downright giddy to find myself rolling through the Arctic with such ease. I called out greetings to the reindeer grazing on the side of the road, and stopped to make a portrait of the curious, unmoving male with the huge rack of antlers. He stood in the middle of the paved lanes, looking at me, as I unclipped from my pedals and talked with him. I rolled across the Arctic Circle in the town of Rovaniemi, Finland, and I thought for the first time that I may even beat my pre-ride goal, arriving on day 19.

I was stronger for all the effort that had carried me into the Arctic, but also deeply exhausted. So, I followed the advice of an old friend, who had once paddled a kayak around Cape Horn and rowed a boat across the Atlantic. As I pedaled north in the Midnight Sun during those final days, he texted from his home on the coast of New England. “Every step is more important now,” he wrote. “Stay focused.” In other words: Be in the moment.

So, I thought not of arriving at the bluffs above the Arctic Ocean, but only at the next village, whether two, or three, or four hours up the road. That, I told myself, was my goal: just get to Sodankyla, for a good night’s sleep, or Ivalo, for a late-morning lunch, or Inari, for water and to restock food on the bike.

Moving like that, I woke in a cabin near the border between Finland and Norway, only 200 miles from North Cape. A south tailwind blew even stronger. After a few hours of riding and just before lunch, I began to wonder if maybe I could ride late into the night, arriving at North Cape as the Midnight Sun rose off the horizon, at 2 or 3 a.m.

On the road ahead, I saw the figures of two cyclists, side by side. I closed on them quickly, which struck me as odd, and I realized that it was James and Ceri, a couple from the Lakes Region of England whom I’d last seen in Copenhagen, 12 days before. Ceri looked pale and weak, and understandably so, as she explained she had a bout of food poisoning that triggered intermittent vomiting and diarrhea. I felt a mixture of empathy and relief, sorry for her that she was suffering, glad for me that I was not.

By mid-afternoon, I was alone again, pushing the pace on a two-hour stretch to arrive before closing at what I thought might be the last roadside shop, 80 miles south of North Cape. The sun and breeze were still strong as I rolled up a few minutes before five, and found two Italians, whom I did not know, sitting outside at a picnic table. They mentioned the fresh waffles inside, so I stacked a plate with three and drizzled on blueberry jam. I was already 120 miles into the day, and though I’d been eating all along the way, I was deeply hungry. I grabbed a quart of orange juice to round out the meal. I still felt strong and steady as I rolled north on a ribbon of asphalt that traced the calm blue of the Barents Sea.

Norwegians embrace the idea of “right to roam,” which allows by law anyone to camp most anywhere, even on private property, so long as 500 feet from inhabited buildings. I still thought I might get to North Cape that night, no need to camp at all. Then, I began to yawn, almost uncontrollably, on the bike. I could see that my power was fading, each mile passing more slowly than the last. The road traced the shallow arc of a bay that was scattered with the homes of fishing families. Without much thought, I pedaled across the short grass of a meadow to a low outcropping of rock covered by moss. I knew immediately that I wanted, and needed, to stop for the night. I found myself racing to lay out my gear. I climbed into my bag and bivy. In that stillness, I realized why I had needed rest, as a strong rumble from my stomach made me tense. Moments later I was scrambling to unzip the bivy, opening the screen just in time. I splayed out my arms on the ground, not unlike a wobbly-legged baby reindeer. Facing the moss, I vomited once, and again, and again.

I lay back, resting, and I thought that whatever had triggered the instant illness might pass. But after four or five minutes, I was splayed forward above the ground, vomiting for a second round.

Empty, I remembered exactly where I was, and that I still had 50 miles to ride before reaching North Cape. They would be rugged miles, first with a four-and-half-mile descent and climb through a deep tunnel that connects mainland Norway to the island of Mageroya. Then with two massive climbs up and over the central ridges of the island to the bluffs at the northern edge. I lay in my bivy sack, shaking from chills. It was nearly midnight, the sun drifting above the horizon. I had a distinct moment of ultimate acceptance: I may not make it to North Cape.

I was surprised how at peace I was with that possibility. I had ridden 2,538 miles in 19 days. I had 50 miles to go. And I felt, even more than I had when riding in the rain with a swollen eye, or standing on the soggy mountaintop alone, that arriving didn’t really matter. I had done it. I had ridden moment to moment, understanding that any one of those moments may or may not carry me to the next. And that seemed the best place to be. There in my bivy on the moss, I closed my eyes and slept.

I did not expect that I would wake, as I did, at 4 a.m. in the already bright sun, and feel immediately, as I did, that I would make it. It was not a conscious feeling. But I could sense, as I lay there, weak and shaky still, that I was already on the mend, and that I would not get worse. It was as though my body said to my mind, “you have managed enough. I will take it from here.”

I moved slowly, packing the bag and bivy, pulling on dirty riding clothes for one last day. I had no appetite, but I sat on the low stone perch and slowly mashed down a banana and took slow sips until a 10-ounce can of Coke was empty.

I saw a cyclist rolling up the road toward North Cape. It was Davide, from Italy, and we had been passing one another for more than two weeks. I knew that I would not move faster than him.

I pushed my bike across the meadow to the edge of the paved lanes. I didn’t think of the deep tunnel ahead, or the steep ridges beyond. I took a long look at the blue, still sea. A light wind was rising from the south. I felt weak in the beauty, but I saw it all. I swung a leg over the frame and pedaled, once, and again, and again.

Tom Haines is a journalist and professor at the University of New Hampshire, where he directs the undergraduate Journalism Program. During three decades as a journalist, he has reported in more than 35 countries and on five continents, on topics ranging from coal to cricket, art to revolution. He has spent the year since North Cape 4000 reporting, writing, and riding in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands.

1 Comment

Thoroughly entered your story. At my age of 73 years and an unlikely race director of the Ultra 2024 Ascend Armenia Race or Ride, my own Alone Moments came rushing back overseeing cycling family in their private experiences of my adopted country, Armenia. Everyone told me to cancel the race, after a serious accident that nearly totaled my old 99 Landcruiser. I resisted as I realized these cyclists had made plans and bought tickets trusting ME that a Life Event awaited them. I was the only patrol car and half way through the race the engine blew. Eventually I calmly accepted what I was capable of and that was merely to greet each rider at the finish and provide a family party, which I did. I really enjoyed the read as I continue to create Bike Packing Routes In Armenia for eventual Tours but who knows. I have learned to stay in the moment, embrace it and live out the Story