Steve The Intern

Pinyons, Lions, Pines, and Doubt: 350 miles through Arizona

- ,

- , Adventures

It has been six months since I participated in Pinyons and Pines, a 350 mile bikepacking race through the arid mountains of Arizona. Time heals all wounds, but the fingertips of my right hands are still ever so slightly numb from the experience. Perhaps time heals only some wounds.

The entire Pinyons experience was full of so much beauty. Even now I can feel, via muscle memory, endless swooping singletrack. I can gaze across austere, volcanic 360 degree vistas in my mind’s eye. I can recall the most sublime arrangement of Ocotillo that seemed to defy gravity as it reached skyward. Combined with those memories are the poignant emotions of doubt, fear, and dread that seem to always be with me leading up to experiences like this. I turn all of these emotions and memories over and over in my head, trying still, even after six months, to not be overwhelmed by their intensity.

Pinyons isn’t a race. That’s what the organizers say in the race manual. The other two or three bikepacking not-races that I’ve lined up for over the years have said the same, which always struck me as ironic and puzzling, because with every denial a race issues, also comes a celebration of it’s winners.

The “not-race” is a wink of the logistical and regulatory impossibility of organizing an event that identifies itself as a “race” in the modern era. Bike racing cannot be tolerated by our present culture, governments, and insurance companies. Fun, self-supported group events where people go as fast as possible for days and days on end are, on the other hand, totally fine.

I attended the Pinyons pre-not-race information meeting and athlete gathering on the evening prior to the start. I looked at all the people standing around me. I recognized some of them, but knew none of them. I caught a glance of one of the pre-race favorites, smiling, laughing, and engaging in casual conversation. He looked so at ease, so self assured. Can you imagine showing up to a not-race and having the inherent confidence and swagger of someone who knows that they’ll probably be the not-winner-but-first-to-finish? It was so unrelatable. I was star struck.

The burn of unresolved pre race logistics stung in my chest, nagging me that I really really needed to get back to my hotel room and get my bike packed up. The start of whatever this thing was would be less than twelve hours away. Tick tock. Back to my hotel I went.

I called my wife. I told her how awful, scared, insecure, and not-ready for this event I felt. I told her that I wanted to miss my alarm and sleep in. I wanted to hide from what might go wrong out there, and from letting myself and others down if it did. She’s been through this with me before: Last minute texts from Morocco. Desperate pre-race rain storm Facetime from Girona. Panicked “please pray for me” satellite SOS during a mountain top thunder and lightning storm in Armenia. She did not appear concerned as she listened. It was almost as if she knew something about me that I didn’t yet know about myself, even after having survived all of those dark moments. We all need people in our lives that believe in us more than we believe in ourselves.

I packed my bike with care. Despite my nerves, this was not my first rodeo. I laid out my clothes, shoes and helmet. I choked down half of a burrito, the act itself a small ultra endurance event. I laid in bed sleepless, unaware of the moment that fatigue spirited me away from reality for eight amazing hours before awakening on not-race-day. I pedaled casually three blocks to the starting line.

The crowd had gathered. Participants and supporters. Friendly smiles. Hugs. Nervous intros. Small talk. Newbies, veterans. Full sus. Singlespeed. Enough collective titanium to build a stealth fighter. Masochists with no sleep kits. Juniors with the relaxed look of cheetahs that just woke up from a midday nap but could quickly take down an antelope.

My internal frequency was that of a high tension power lines when all is quiet and the air is damp. Bzzzzzz. Crackle. Bzzzz. 1500 megawatts of anxiety, enough to power 1.5 million homes, yet visibly undetectable, only audible.

The neutral start lost its neutrality. The leaders darted away into the thin forest. I looked down. I have a power meter. It isn’t there to tell me how awesome I am, it’s here to tell me that I’m over cooking it, already, not yet even at the base of the day’s first summit climb.

I told myself that at Pinyons I would ride within myself. I told myself that nobody here was my competitor. I was my competitor. I was here to focus on a certain goals:

- Take care of myself.

- Listen to my inner voice

- Fight my built in negative tendencies

- Master my emotional swings

- Find joy out here

- Ride to my potential

I needed to slow down. 40 minutes later I was high on the mountain, near the top of the big climb. I was riding too hard. How could I not? The early miles of any event are so full of euphoria and release. Holding those emotions in check takes more willpower than I have power over. Who would have thought that the challenge of ultra racing isn’t speeding up, it’s slowing down?

A group of about ten was up ahead on the mountain, and then starting down the other side. I wanted to chase them, but I also knew that I physically couldn’t. I am not a cheetah. I am not a hare. I am not a thoroughbred. I am a donkey.

I eventually began the descent myself. It became increasingly treacherous. Race-ending rocks and small drops were plentiful. Riders approached from the rear and passed me, touching the earth only long enough to vector from impossible line to impossible line. Again I was star struck by their skill. I walked, and stumbled, and did the one legged tripod thing more times than I would care to admit. I got down the other side of the mountain. It wasn’t pretty, but to this day I’m the proud steward of two unbroken collarbones.

Bikepacking racing, or ultra racing, is for me an exercise in humility. I don’t think that the truly great racers, the superstars of the sport, see it that way. They brim with confidence and swagger. They dispense pearls and protips. They look fresh all the way out on day seven, and even when they don’t look fresh, that looks beautiful too. They set lofty goals and ride out to meet them boldly. They’re the best of us.

I do not begrudge these top athletes their charisma and giftedness, but nor can I relate to it or comprehend it. In my darker jealous moments I wish I could be like them, unflinching and unaffected by adversity, uncrackable emotional vaults. What would it be like to be human Gore-Tex; to lock in and watch fear, anxiety, and self doubt just bead up and roll off?

The day pressed on. Pinyons and Pines traverses large sections of Arizona Trail singletrack. I was new to the phenomenon, and it’s a tricky beast to master. At one moment you’re flowing through groves of trees on soft volcanic soil, and in the very next your front wheel is gone and you’re floating on a bed of tiny volcanic pebbles aggressively exfoliating your skin. Humility, Stephen! Respect the trail. 15 minutes later, repeat.

I started catching riders every 30-60 minutes as the sun beat its arc across the sky. A singlespeeder here, a guy who sent it off a drop and crashed there. This helped my morale because, having ridden alone for a fair bit, I had no sense of how to rate the progress that I was making. My thoughts drifted to mountain lions, my favorite muse. Do they stalk you in the middle of the day? Do I fundamentally look like a wounded animal? Diseased, maybe? The outcropping that I rode by had a lovely shape. If I were a mountain lion I would attack me there. Honestly, “he died doing what he loved” isn’t the worst possible outcome in an event like this. Better that than falling down the stairs at work.

At precisely mile 58.5 I arrived at my first resupply of the day. Over 50 miles of constant AZT singletrack had taken their toll. The fatigue of it all was hitting deeply. I didn’t need to resupply. I had a stash of food and even water large enough to make a prepper proud. Despite that I decided to reward myself with some sugary treats for having come this far in the race, and in life.

As I arrived at the store I spotted the aforementioned pack of juvenile cheetahs. Junior racers are a whole vibe. Nothing about them shows of wear, or of wisdom. I’m jealous of the former. I try to be fit, but I can grab a fist full of my own belly fat at will. Per the lack of wisdom, the Juniors were strewn all over the outside of the store, lounging in the sun. They were in no rush. They had beat a hasty pace to mile 58.5, and then celebrated their achievement by pissing it all away, as one does after felling an antelope. I, on the other hand, put on a clinic in masters-pilled efficiency. 2 Snickers, 1 Gatorade, one Coke (with resealable cap so I could nurse it while I rode). Bottles topped and off I went, having just passed five of the fastest creatures in the animal kingdom. I didn’t know it at the time, but I was now sitting at third wheel in the not-race.

Miles 58.5 through 99 were an absolute nothingburger, in the way that a world class ribbon of singletrack trail, combined with the most sublime riding weather imaginable, could be taken for granted because they were merely something that must be moved through on the way to the final destination. This is the essential crime of racing, in name or in spirit. The act of pushing your own boundaries and discovering more about yourself in a bikepacking race reduces your interactions with the places you pass through to a form of geographic and sometimes cultural prostitution. Some people take no issue with prostitution. I rather do, but I don’t take issue with bikepack racing. I forge loving relationships with places and people on different types of rides and tours. Today I’m here to get dirty and go, go, go. $50 to the Arizona Trail Association. $50 on the bedside table.

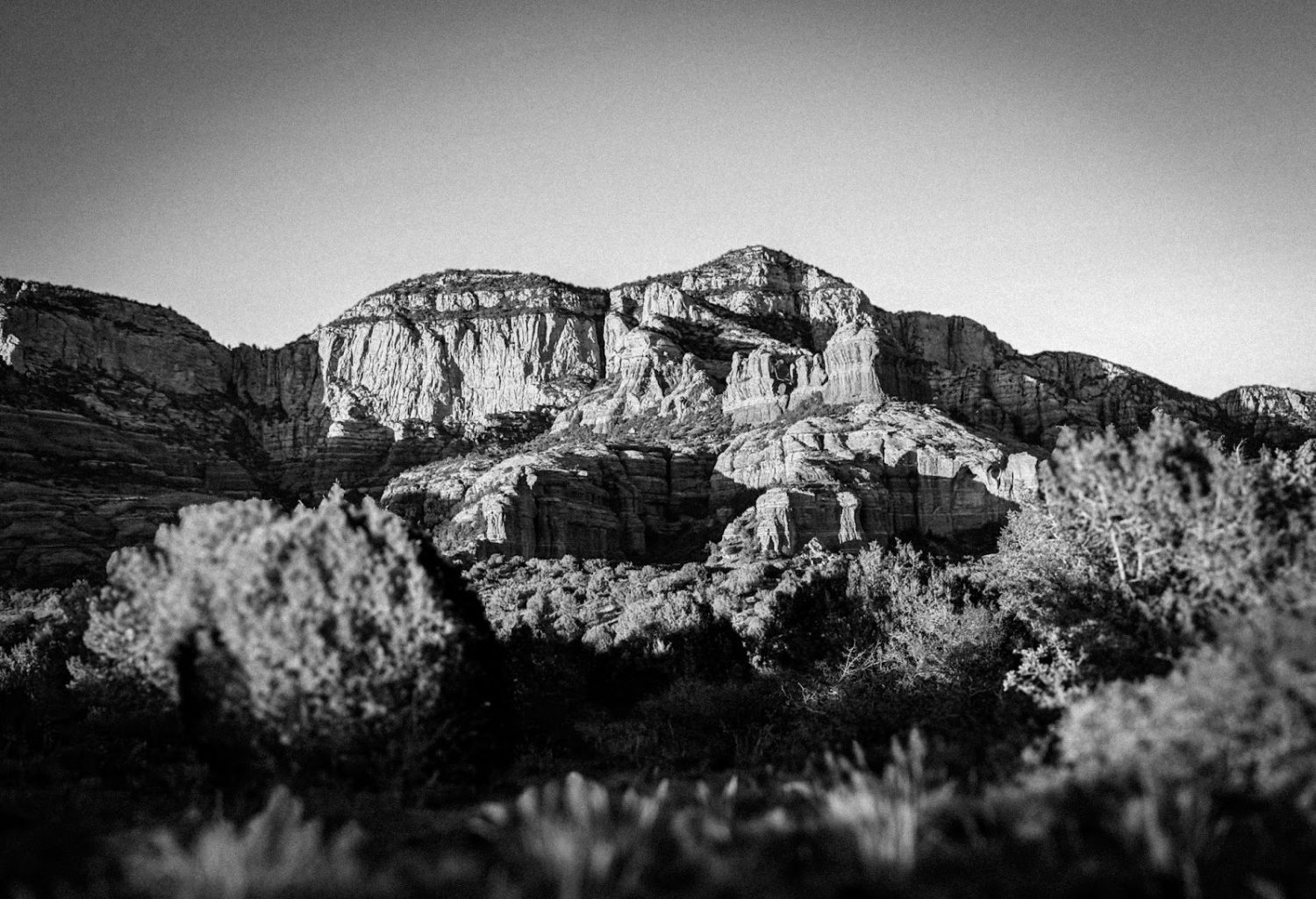

I spot a rider up ahead, darting in and out of the trees. He appears for a moment then takes a turn back out of sight. Instead of chasing, I make no changes to my pace. This rider is not my competitor. He’s someone out here racing with me, someone who simply will or will not be able to complete the course faster than me. We ride side by side for a while. It was a wonderful bit of human contact and camaraderie. He’s absolutely shelled. Digestive issues. Altitude issues. Perhaps also pacing issues, but who am I to judge? I drop him. Now I’m in 2nd place. Minutes later he drops me on a particularly jarring and unpleasant descent into Sedona. Now I’m back in 3rd, but made richer from having met him.

3rd place is something to celebrate with a burrito stop. Sedona would be my last chance to hoard more calories until I arrived in Flagstaff, the halfway point of the race, some seventy miles later. It is so jarring to exit the mind space of an endurance bike event and drop into the carefully curated spa fantasy land of Sedona. The endurance state of mind is one of constant discomfort and self denial. Sedona is a place built for exactly the opposite. I found it alluring and repulsive at the same time. Deep down I crave comfort and rest from the world and it’s stresses on a primal level, yet here I am participating in an act of near self harm in a willful attempt to touch one of life’s raw nerve endings.

Sedona does have an abundance of lovely roller coaster singletrack, combined with just enough techy stuff to repel the urge to find a shady bush and take a nap. I was lost in it for a couple of hours, sometimes close enough to clusters of stucco mansions and HOA fees that I could smell them. Only a switchback later I would once again be mostly lost in the gorgeous rock formations and beautiful flora that are abundant there.

I emerged back down on the highway and paused for a moment. Highways signal gas stations. Gas stations signal high fructose corn syrup. 3rd place rolled up behind me. Wait. 3rd place? I thought I was in 3rd? Turns out 2nd place had heeded Sedona’s siren call longer than I had. He let me know that there would be no more corn syrup found on the route until Flagstaff, so we best be at it. He pedaled off ahead of me. I paused. Pangs of anxiety. I was in a bit of a pickle, having mis-judged my water situation before such a long, dry, empty section of the course. Around me were improbably watered islands of landscaping, and hotel lobbies, and schools, but I was too shy and self conscious to walk in to any of them and ask for help. In a lucky turn of events a leaky fire hydrant bubbled, creating a cold oasis of Biblically-spontaneous hydration right as pavement turned to dirt. I filled up and drank deeply. It tasted of heavy metals and civilization.

As the sun began setting for the day and a somber mood set in. The full weight of what I had signed up for began to register. Darkness would come soon, and with it mountain lions, and with them the end both of beauty and life. I found myself depressed. I hate riding through the night.

“Damn, Stephen, you’ve got to snap out of it. You’ve got to work on the self talk. You need to remember that you want to be here, in these moments, confronting them, passing through them, and prevailing over them”.

This stuff is hard to control. It’s hard to stay on top of. Staying on top of it is essential. I wasn’t out here working on bikepacking skills, or race skills, I was working on life skills. People talk of mastering themselves, but mastering one’s self isn’t only an abstract idea, it’s a thing you have to do through willful action.

Darkness now. Up ahead in the dark I could see 1st place and 2nd place close together. It was pitch black but their headlights dimly lit the hillside. They occasionally swept back down into the valley haphazardly like lighthouse beams in disrepair. They looked quite close, but I knew that they were on one of the most notorious climbs of the race. A half mile as the crow flies seemed like it would take two hours to cover. Eventually I lost sight of the lead beam as I began my own back and forth up the mountain. Below me twinkled other headlights of other racers who were no doubt reeling my tired body in. The headlights up the mountain represented strength, widening their lead over me. The headlights behind me represented predators, hunting me down. I felt total self doubt. I couldn’t eat, my stomach was sour. My energy was draining. I couldn’t control my emotions any longer.

It was only 10pm, but I had lost control of the situation, like a rope that’s slipping through your hand. If you try to grip it again you know that it will burn you. I decided right then and there to pull out my mylar bivvy sack, stuff my sleeping bag into it, and climb in. I knew that I needed to reset my body and my mind. It felt absurd to sleep this early in the race. The stallions ahead of me had stated that they had no sleep kits and no plans to sleep at all. This ultra race, at merely 350 miles, wasn’t genuinely long to them. But this wasn’t about them, it was about me. I needed to listen to myself. I needed to take care of myself. These were my goals for Pinyons, and these moments of decision were how I would accomplish them.

The sleep was piss. The breeze loudly crinkled the bivvy in my ears. The anxiety of sleeping when I should be racing sat on my chest. One by one racers caught and passed me, maybe ten in all, and as they did they each burned my retinas through my eyelids with their LED headlamps. I felt their judgement.

“What racer sleeps after only 15 hours of racing?”

I do, but I’m not a racer, and this isn’t a race.

Eventually the sleep exercise became pointless. I packed up and soldered on up the mountain. My stomach was still sour, as was my mood. The climb was shorter than I had thought it to be, and soon I was at the top. The wind died instantly. Whoops. Small miscalculation there. This would have been the better place to bed down. As that thought landed, my gaze locked on a small group of sleeping riders, and then a short time later another one. Oh. I guess other people needed sleep too? Maybe I wasn’t such a loser?

This was the darkest part of the race. This was probably the most remote riding I did at Pinyons. My headlamp swept left and right, daring the lions to show themselves.

“I know you’re out there. Let’s get this over with.”

Eyes blinked back, reflecting my beam. Some, I later learned, were almost certainly deer. But others were very solitary. These eyes did not blink at all. They didn’t move. They weren’t intimidated by me. Funny thing: as I looked at them I wasn’t intimidated either. In the abstract, mountain lions are my single greatest primal fear. In the moment they were simply creatures trying to exist just like I was. I’ll never know if I was looking at jack rabbits, deer, bobcats, owls, or cougars. In recent years jaguars have also once again been spotted in Arizona. I’m pretty sure at some point at Pinyons I stared into the eyes of a killer and met its gaze.

The night was cold. Fatigue manifested more practically. My eyes saw things that weren’t there and the line between awake and sleeping was erased. How do the pros go for 48 hours of racing without sleep? What makes them special? Willpower? Genetics? Youth? I lacked that exact trifecta, so I considered sleeping once again. My pre-race agreement with myself was that I could sleep up to four hours per night, and I had only cashed in two of those hours earlier in the evening. A second attempt at a reset seemed both a crazy, self indulgent idea, and also exactly what the doctor ordered. For sure I’d already squandered my way out of the top ten, so what was the point of any of this any longer, if not to have as positive of an experience as possible?

I slept on soft frozen grass, in a grove of pines just off the road. This time I left planet earth behind, and went to that special type of dream state where things get most fantastic and absurd. The entire experience was delicious. The decision to sleep for a second time was one the most accidentally brilliant that I’ve made in my entire amateur bike racing life.

I woke up ready to rumble. I had once again been passed by more riders, but now I was liberated from the compulsion to defend my standing. Racing against one’s self is often a high minded stated goal, but one more spoken than acted on. Now I felt like I was actually doing the thing. At 5am on Day 2 of the not-race, I re-started Pinyons and Pines with a totally different mind.

Really riding for yourself is quite liberating. Things just feel more fun. The monkey is off your back, or your chest. The pressure of external expectations is gone, and you can be totally honest with yourself as you decide what the new objective is going to be. My objective was to get down to Flagstaff, the midway point, and feast on gas station roller taquitos.

Pinyons had an interesting course layout this year. The shape was a figure 8, with Flagstaff being the start and finish of the race. The midpoint of the 8 was also in Flagstaff. After you had done about half of the course, you would arrive exactly back at the start. Your car would be there, maybe your house would be there, or your hotel. If things were going poorly, or even if they were going fine, you had the opportunity at that moment to bail on the second half of the race. Even if you did decide to quit you could be genuinely proud of having ridden 184 miles already. That’s no small feat! Many did bail out in Flagstaff. My strategy was to blast through the turn-off where you quit. If I could make it past that point, I was pretty sure I could complete the 2nd loop and make it back to the finish.

A couple of hours later the quit spot was behind me, and I was triple guessing my life’s choices. I was halfway up Elden mountain, and my legs refused to turn the cranks. Big Bang was the name of the trail I was on. On a normal ride the techy step ups and large rocks that littered it would have been entertaining and enjoyable, but in the present moment my mind and body couldn’t make sense of them. I dismounted and walked on anything steeper than about 4% gradient, which was pretty much the entire trail. You just have to accept how weak you are in those moments. There is so much ego involved in endurance sports. You craft your body and fitness carefully, sometimes obsessively. You feel strong. You are strong. But really, after not very many hours you aren’t strong at all. Whatever you called strength was really just glycogen stores. My glycogen left the chat the day prior, and was not seen again for weeks after. But once again this is why we’re really out here. It isn’t to be strong, it’s to be weak, and humbled, and to have to grapple with that. Is our physical strength the most true thing about us, or is our mind where our truths are determined?

I made it up and over Elden the second time. I don’t know how. It doesn’t matter how. This is endurance racing.

A funny thing happened on the backside of Elden. I found out that, as weak, fragile, and vulnerable as I felt as a person, the will and effort that I had managed to muster had added up to me once again being in 3rd place in the race. I didn’t understand the dots of representing each rider on the map as I stared at my phone. Where had everyone gone? I thought I was in maybe 10th or 12th position. Long distance racing is a mystery. While I was sleeping off my fatigue, lamenting my unimpressive pace, or shuffling up Mt. Elden that morning, other racers were out fighting their own bodies and their own demons. Many were overcome. The day one race leader had scratched due to some form of exhaustion. More than one of the young cheetahs found themselves vomiting in the bushes. Others simply succumbed to the sweet, sweet call to end it at the halfway in Flagstaff. It wasn’t that I had overcome any of them, they had simply, and for their own reasons, left the race.

Endurance isn’t about speed. Endurance is about enduring.

An hour later I caught and passed 2nd place. He was such a strong and smart rider, someone who deserves genuine admiration, but he went off course in error, and in doing so saved me from the same fate. His loss was my gain. I pulled away from him on a gloriously long, hilariously fast downhill. He had merely one cog, and I had twelve. None of it was fair. It was simply the way that it worked out.

The race organizer sent us up a hot, miserable, steep out-and-back climb called O’Leary. If this sort of bike ride weren’t arbitrary enough, an out and back like that really drove the point home. None of this stuff makes rational sense to do, but we find so much meaning in the doing of it. We really are a weird bunch.

I enjoyed my residency in 2nd place, and puzzled on the fact that only a single rider stood between me and the rarest of all rare things in bike racing: A win. I have won things at times in my life, but I have not won things in a good while. I’m 47 years old now. Winning is no longer the main course for me. It isn’t a probability, and it’s less and less a possibility. At every moment the young lions are eying the old lion, sizing it up, carefully evaluating if it is possible to unseat as head of the pride. Inevitably that moment comes and the old lion is dispatched. I’m at the exact age where I still know how it feels to be young, and I want to continue to act like I am, but am also realizing that “old” better defines me. Let’s not beat around the bush. This sucks. The minute you are born you have to start engaging with the fact that the experience of being vital and alive on this blue marble will come to an end. Bikepacking races are a good opportunity to not just think about this, but also deal with the repercussions of it. Age isn’t an abstract concept, it’s rubbed in your face by the younger guy who’s five to six insurmountable hours ahead of you on the same course. 1st place wasn’t coming back.

I numbed my thoughts on mortality with one of the finest naps of my life. The air temperatures were that of a warm blanket. The afternoon light was dappled through the pinyons. The earth around me wasn’t dirt, it was volcanic pumice soil. It was soft like piles of popcorn burned to bare carbon a thousand years ago. I didn’t need a bivvy sack, or a sleep kit, or a jacket. I simply lay my bike down, burrowed my backside into the soil with a wiggle, and drifted off to sleep for a blissful 30 minutes. The strategy here was to bank some sleep when it was logistically easiest to do so. I wanted to finish that night, in about 12 hours, and I wanted to do so with no more major stops. Somewhere during the nap, 3rd place passed me once again, but nothing mattered. I laid there in the black pumice and became singularly at peace with all of my life choices. This is why I was out here. Peace in the eye of the storm.

Back on the road the boredom of long, flattish miles hit. I flicked my phone out of airplane mode to download some podcasts or music to pass the time. My text messages lit up instantly. My buddies back home were following dots too.

“The race leader just scratched, you’re in 2nd place, 1st is just up the road, go get him”.

A jolt hit. Adrenaline. A dormant instinct that I had repressed for a long time flickered to life. It’s easy to live with 2nd place if 1st is 5 hours ahead. It’s also easy to live with 3rd place if need be, because that was also beyond my wildest dreams. But missing 1st place by a half hour because I simply couldn’t be bothered to get my head in the game: That seemed like a crime against myself. The opportunity to win at anything is so rare, so fleeting, and I think it deserves to be respected when it shows itself to you.

All of a sudden the not-race was for me, definitely a race.

I had time to consider the overtake: He was on the singlespeed, I had gears. He was on flat bars, I had a drop bar 29er with aero bars – precisely for long doubletrack miles such as these. I hunkered down and got to work on the cranks until I saw his dot emerge on the horizon, right at Shit Pot Crater, a black monolith that defines the northernmost point of the course. His speed was about 10 mph. I brought mine up to about 24. I wanted to pass him suddenly and decisively so that he would be discouraged from making chase. I wanted to look fresh and strong although I felt the opposite. I wanted to appear unbeatable.

“Look at that guy, he’s a cheetah. Why chase?”

Was it a fantasy or a strategy? It was both, and I played it. I slipped by the lead rider suddenly and he didn’t respond as I waved. A downhill ensued. I dug into the stirrups. Keep faking it, Stephen. Look strong. Get a gap. I was completely faking it.

I hung a sharp left into a truly soul destroying headwind, but It didn’t matter. I’d gotten a gap.

I was, absolutely, improbably, in position to win the 2025 Pinyons and Pines bikepacking race.

An hour later a truck approached on the horizon in front of me, kicking up a cloud of dust behind it. There were two figures in the cab, and there was a bike hanging out of the back of it. The scratched race leader had hitched a ride back to town with a kind local farmer. As they passed I caught a glimpse of him. He was the guy I had rode with just before Sedona. He was the race favorite from the pre-race meeting. He was the one that looked confident and self assured. He was the one that I envied most. He had the win all but in the bag, but in his absolute and total commitment to the effort, he had gone too deep. He had bankrupted his body in the most noble way. I admire that because I am not capable of it. Valhalla welcomes people like him.

I feel like a thin version of an ultra racer. The qualities that I admire about people who win don’t feel innate to me. I don’t feel strong. I don’t feel assured. I can’t control my emotions. I’m afraid of putting myself all the way out there and risking it all.

But then again, I’m still out here. I’m out here because the act of testing yourself and setting personal goals can be common to anyone. I find so much joy and beauty in it. Sometimes you scratch, sometimes you end up mid pack, and sometimes you cross the finish line first.

At 2:30 AM the next morning I pulled up on my bike to an empty parking lot in Flagstaff. I was delirious, overjoyed, and blissfully spent. I had reached the finish line first. There were exactly zero people there to greet me for the next 15 minutes. This seemed fitting, and I was able to sit alone with the moment. I would have cried were anyone around to share it with.

Thanks to Wyatt Spalding for coming by the finish and taking this photo.

Pinyons and Pines was satisfying in a way that I don’t know how to fully convey. It wasn’t about surviving, or even winning. It was about turning abstract goals into reality.

- Take care yourself

- Listen to your inner voice

- Fight those negative tendencies

- Master emotional swings

- Find joy out here

- Ride to your potential

1 Comment

Congratulations on the win! Respect and appreciation for the vulnerability and humility reflected in your words.